In a

post earlier this year, I mentioned a recent experience I had at St. Petersburg's

Dalì Museum: seeing some of the artist's early works, what was most striking about them was how derivative they were. Several of Dalì's paintings from the late 1920's looked like lesser works of whichever contemporary he was currently in the thrall of, including many that bore remarkable similarities to Picasso's and Miro's works. It was not until the following decade that one of the most distinctive artists of the twentieth century actually found his own style – when Dalì started making paintings that looked like Dalìs.

The delicate subject of inspiration versus copying in the cooking world is one

I've explored often here. Few, if any, artists start their careers with a fully formed vision of their style together with the technical ability to execute it. There's plenty of exploration, experimentation, and, yes, copying, that usually comes first. And I suspect it's much the same in the kitchen.

The complicating fact is that in the restaurant world, chefs generally aren't doing it in the privacy of cloistered artists' studios: they work in a public setting, serving up their creations on a plate to paying customers. Does it matter if those "creations" are sometimes very similar to dishes actually created by other chefs? If the primary focus of a restaurant meal is flavor, then perhaps not: a great-tasting dish tastes great, regardless of who thought it up first. And indeed, many outstanding dishes are the product of one chef taking another chef's idea and making it even better.

Some chefs unabashedly fess up to copying others. The

Mission Street Food (the pop-up precursor to

Mission Chinese Food) book talks about how they did "homage" dinners centered around their "phantom culinary heroes" including Rene Redzepi. Not having actually been to

Noma, they had to "piece together our recipes by poring over images online and culling bits of information here and there, not unlike teenagers learning about sex from porn." In

Fancy Desserts,

Del Posto's punk rock pastry chef Brooks Headley talks about how it can even happen subconsciously. He draws a cooking:music analogy between Noma and the Dead Kennedys as having unique and "un-rip-offable" styles, then notes how that didn't stop everyone – including himself – from trying to copy Noma: "For a long time, seeing sorrel and sea buckthorn berries on fine dining menus really pissed me off.

(You can't rip off the Dead Kennedys, man!) But then I realized that I was doing it, too. I was so guilty, and I didn't even realize it." The incriminating evidence: pickled green strawberries.

So there shouldn't be any shame in it. But if you are copying (or paying homage, depending on how negative or positive a spin you wish to apply), how much, if any, credit ought you give? Should you do like David Kinch does when he serves an "

Arpege egg" at

Manresa? Can you be coy, like

Pubbelly when it lists "

dates AVEC chorizo" on the menu? Or is it sufficient to just assume that knowledgeable diners will be in on the joke (and oblivious diners won't care)? And with creativity an increasingly common component of the marketing pitch for new restaurants, what of Ferran Adríà's maxim, "

creativity means not copying"?

I don't know all the answers. But I do know when something looks and/or tastes a lot like something I've had before. So, inspired by

Us Weekly (and with a hat tip to

JSDonn), here's my version of "Who Wore It Best?" Let me know what you think.

Who Wore It Best? (Round 1)

1.

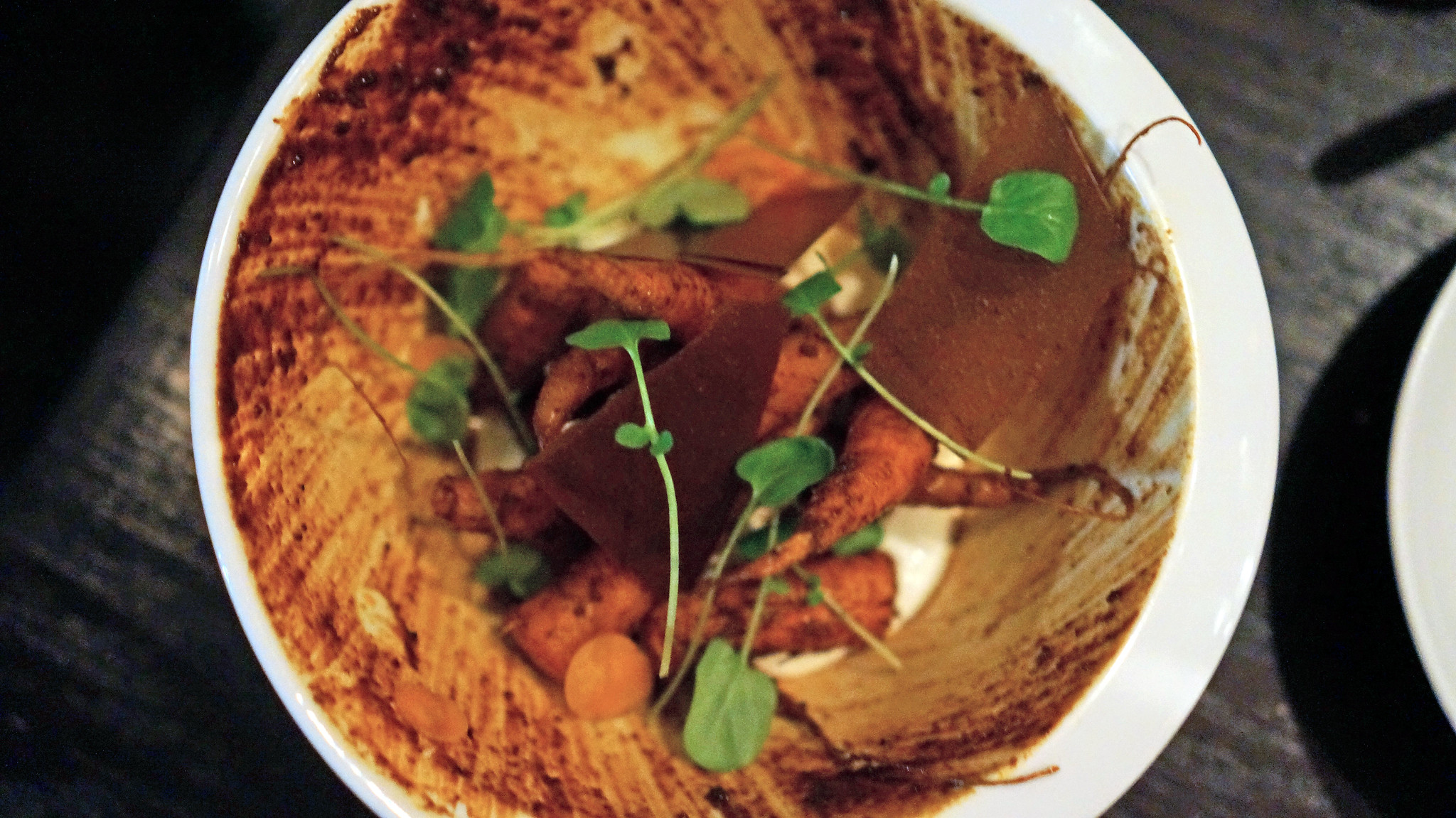

Roasted baby carrots, mole, hazelnut, yogurt, za'atar at

Vagabond Restaurant, Miami.

2.

Roasted carrots with mole poblano, yogurt and watercress at

Empellon Cocina, New York.

My latest mantra is that "carrots and yogurt" is the new "beets and goat cheese" – a combination that seems to appear on every new menu in some form, and which despite its increasing ubiquity I'll still order because it's usually pretty darn good. But the similarities between a dish at chef Alex Chang's new Miami restaurant, Vagabond, and Alex Stupak's Empellon Cocina in NY go further: not just the carrots and the yogurt, but also the distinctive use of Mexican mole sauce, plus the tepee presentation, though some other components differ. (Note: Empellon has been

serving this dish since at least 2012).

(continued ...)