▼

Wednesday, April 26, 2017

Cobaya Olla with Chef Scott Linquist

Mexican cuisine is one of several that gets saddled with the "soft bigotry of low expectations." The common perception is that it's all chips and salsa and guacamole, tacos and burritos and fajitas, with maybe some tequila shots, mariachi bands and sombreros mixed in for good measure. In fact, it's an incredibly complex and varied cuisine, which is finally starting to get the attention it deserves in the U.S.: witness the success of Enrique Olvera's Cosme in New York, or Alex Stupak's Empellon, or places like Taco Maria and Broken Spanish in L.A., or Californios and Cala in San Francisco, or Rick Bayless' restaurant empire, plus new Chicago places like Dos Urban Cantina and Mi Tocaya. I could keep going; but instead, let me bring this back home.

Because someone is trying to help Miami catch up. At Olla, Chef Scott Linquist's new restaurant on the west end of Lincoln Road, you'll find a menu that goes well beyond the customary tropes, ambitious both in its pursuit of the authentic flavors of Mexico and in finding modern ways of presenting them. My first visit to was in December, only a week after they'd opened, and I was pretty excited by what I found. Not much later, we started to work on putting together a Cobaya dinner, which came to fruition last week.

(You can see all my pictures from the dinner in this Cobaya Olla with Chef Scott Linquist flickr set).

Everyone was welcomed with a house cocktail – a variation on the flavors of a Moscow Mule, which they dubbed the "Oaxacan Burro," featuring Alipus mezcal, a ginger and epazote shrub, a slug of ginger beer and a squeeze of lime. This was prelude to a mezcal sampling courtesy of XXI Wine and Spirits, a distributor for Alipus, which poured three different "single village" offerings. I'm becoming a real fan of mezcal, which is almost exclusively a craft, small-production product, and which can show a fascinating variety of styles and flavors – some with a clean, almost sake-like purity, others floral, or fruity, or grassy, or smoky, or all of the above.

Once our group of fifty was seated (we took over the restaurant for the night), dinner started with a round of bocadillos, or snacks.

Yes, chips and salsa. But not just any garden variety salsa: four different salsas, starting with a basic salsa fresca, and also including a fresh, raw salsa verde (with some bright, fragrant mint in addition to the usual cilantro), a deeper-flavored, charred tomatillo and habañero salsa verde, and a hearty, red brick hued version with pasilla Oaxaca chiles[1] and roasted pineapple. Plus guacamole, because yes, everyone loves guacamole.

(continued ...)

Tuesday, April 18, 2017

first thoughts: Dashi | Miami River

Last month, I had the good fortune to be invited to an event at the Japanese Consulate in Miami, extolling the virtues of washoku, or the traditional cuisine of Japan. The event was hosted by the gracious consul general, Ken Okaniwa, but the headliner was chef Shuji Hiyakawa, who provided a live-action sushi-making display.

I had a feeling we were in good hands when Chef Hiyakawa started with the preparation of the rice, noting how every component is essential to the finished product: the blend of two vinegars he uses to season the rice, the wooden bowl in which it's prepared, which retains the right amount of heat and absorbs the right amount of excess liquid, the manner in which it's mixed, so that all the grains are seasoned, and neither too starchy nor too loose.

With the rice made, he went on to break down an entire loin of bluefin tuna. Given the depleted state of the species, I really would have preferred to see just about anything else on the cutting board. I suppose between its immense popularity in Japan, and its increasing popularity here in the U.S., and many diners' lack of understanding of the different cuts sourced from the same fish – the fattiest o-toro, the medium-fatty chu-toro, and the lean maguro – I understand why they would choose this for the demo. But particularly given the traditional washoku theme, I would have been grateful for a presentation on the virtues of the many other varieties of fish and seafood that can be made into sushi. After all, the bluefin obsession is actually a relatively recent thing – in Japan, it was mostly thought of as a trash fish until the 1970's (for further reading: "From Cat Food to Sushi Counter: the Strange Rise of the Bluefin Tuna," which is mostly based on Trevor Corson's book, "The Story of Sushi").

Nonetheless, it was an informative demonstration, and even better, was followed by an assortment of prepared dishes, which were accompanied by more than a dozen Japanese sakes, none of which are currently available for distribution in the U.S.

(More pictures from the event in this Culinary Secrets of Traditional Washoku flickr set).

As it turns out, this would not be the only opportunity to try Chef Hiyakawa's handiwork; he was only weeks away from opening his own restaurant in Miami. The chef, who hails from Fukuoka, Japan (where his father had a noodle shop), came to the U.S. to work for Masaharu Morimoto at his flagship Philadelphia restaurant, where he was executive sushi chef for several years. More recently, he wound his way to South Florida, until recently working as executive sushi chef at Kuro in the Hard Rock. He's now running his own place, Dashi, in a space inside the River Yacht Club.

(You can see all my pictures in this Dashi - Miami flickr set).

While his demo at the Japanese Consulate may have focused on traditional Japanese cuisine, Chef Hiyakawa's restaurant bridges old and new. In addition to nearly two dozen sushi and sashimi options, the menu includes prepared dishes that are both traditional (wagyu beef sukiyaki) and contemporary (white fish tiradito with sudachi juice and olive oil).

We sampled a couple of these prepared dishes while awaiting our sushi order. A salad of cha-soba (green tea noodles) was speckled with edamame, batons of asparagus, and slivers of shiitake mushroom steeped in soy sauce, all napped in a lightweight but umami-loaded variation of the restaurant's namesake dashi broth. A "House Poke Salad" was a rather un-poke-like but tasty combination of cubed tuna, tomatoes, avocado, cucumbers, and micro-greens in a ginger and miso dressing. It was a pretty sparse plate to bear a $25 price tag.

Mrs. F and I ordered an assortment of sushi which was presented all at once (pictured at top). Our order included kinmedai (golden eye snapper), madai (sea bream), hamachi (amberjack a/k/a yellowtail), aji (horse mackerel), shima aji (striped horse mackerel), masu kunsei (smoked sea trout), sake (salmon), botan ebi (sweet shrimp), ika (squid), anago (sea eel) and tamago (omelet). You see? There are a million wonderful things in the sea to eat other than bluefin tuna.

There were a few things I really liked about this.

First, Dashi's rice is indeed very good: well seasoned but not overwhelmingly so, with each grain distinct on your tongue, neither dry nor overly moist and clumpy. This was all the more impressive given that an order of this size, served all at once, necessarily has to sit for a time as each piece is being assembled (more on that later). Second, each piece was already brushed with nikiri, a glaze usually made of some combination of soy sauce, mirin, dashi and sake. Our server actually discouraged the use of a soy sauce dipping bowl at the table, as each piece had already been properly seasoned. Some also had been given a little extra garnish – a daub of miso on the salmon, freshly grated ginger on the aji, a shiso leaf tucked under the ika and a sprinkle of black salt on top. And finally, the fish – much of which is flown in from Japan, with its particular provenance listed on the menu (hamachi from Kyushu, kinmedai from Chiba, shima aji from Wakayama) – was very good.

A couple pieces of our order – the uni and the ikura, both from Hokkaido – were served separately in little bowls, with a small mound of rice, a sheet of nori, and the neta, almost like a free-form nigiri or a miniature donburi. This was kind of perfect, as I often treat these as my "dessert," and they were a couple of the best bites of the evening,

It's not Naoe level quality, but Dashi is probably close to on par with what I've had at Makoto or Myumi. Prices are steep, even more so than Makoto, which ain't cheap: other than the tamago on the low end and Hokkaido uni on the high end, our order ran between $7-10 per piece, compared to mostly $5-7 per piece at Makoto. They have a nice selection of sakes and Japanese beers to accompany your dinner, as well as some Japanese inspired cocktails.

Dashi's location, as a sort of restaurant-inside-a-restaurant within the River Yacht Club,[1] is itself a draw, with a vista that looks across the Miami River in one direction towards downtown and in the other towards Brickell, including the recently re-lit "Miami Line" designed by artist Rockne Krebs which stretches along the Metrorail bridge. Unfortunately, there is one glaring omission from the design of the restaurant, which otherwise is a pretty slick and scenic indoor-outdoor space: there's no sushi bar. And not to sound like a prima donna, but this is very nearly a deal-breaker for me. If you want good sushi, there's simply no substitute for being right at the counter, with each piece passed across to you as it's made. The rice can be packed looser, the neta doesn't sit and dry out as other pieces are made; it's just impossible to duplicate that when you're making a dozen pieces at a time which sit for several minutes before they get to the table.[2]

But the combination of good food and a waterfront view is surprisingly elusive in Miami; it's a combination Dashi achieves, if you're willing to take the view as a trade-off for the absence of a sushi bar, and pay a premium for it.

Dashi

401 SW 3rd Avenue, Miami, Florida

786.870.5304

[1] This is an intriguing piece of property, situated on the Brickell side of the Miami River nearly underneath I-95 and next to Jose Marti Park.The main restaurant there apparently has a "rotating chefs-in-residence" program, though what I mostly noticed while walking through to Dashi was the "untz untz" music and what appeared to be a session of Advanced White People Dancing Badly on the outdoor dance floor.

[2] Of course, the converse isn't necessarily true either: everything can get screwed up even when you're right at the sushi bar. A few weeks ago I visited another recently opened Miami sushi den, which had a beautiful 8-seat sushi counter manned by five hard-working sushi chefs. It also had one of the most interesting and exotic selections of fish that I've seen offered in Miami. Unfortunately, the rice was so bad – dry, under-seasoned, stiff – and much of the fish was also so dried out and consequently lacking flavor, that I'm reluctant to even give the place a second try. It's a shame, because it was an ambitious and exciting assortment that otherwise would be right in my sweet spot.

[2] Of course, the converse isn't necessarily true either: everything can get screwed up even when you're right at the sushi bar. A few weeks ago I visited another recently opened Miami sushi den, which had a beautiful 8-seat sushi counter manned by five hard-working sushi chefs. It also had one of the most interesting and exotic selections of fish that I've seen offered in Miami. Unfortunately, the rice was so bad – dry, under-seasoned, stiff – and much of the fish was also so dried out and consequently lacking flavor, that I'm reluctant to even give the place a second try. It's a shame, because it was an ambitious and exciting assortment that otherwise would be right in my sweet spot.

Saturday, April 15, 2017

best thing i ate last week: fried chicken sandwich at La Pollita

There's yet another wave of taquerias opening in Miami these days, so many I've given up even trying to list them, much less sample them all. But last week I did stop in on La Pollita, which is currently operating from a trailer parked in the Midtown Garden Center. The backstory is intriguing: chefs Luciana Giangrandi and Alex Meyer worked at some pretty highfalutin places before this: Eleven Madison Park (just named as "World's Best Restaurant" by the suspect but influential 50 Best list), its sibling the NoMad, Scarpetta in Manhattan, Animal in L.A. Which made me wonder – what are these folks doing running a taco truck?

Making really great food, it turns out. They've got a short list of tacos, served on fresh tortillas pressed from masa supplied by Miami masa maestro Steve Santana (of Taquiza), and the cochinita pibil I tried was very good. But the standout item was the fried chicken cemita. A hot, crispy, juicy tranche of fried chicken. A crunchy, vinegar-laced, herb-flecked cabbage slaw. A dollop of mashed avocado for some richness. A creamy, mildly spicy Valentina aioli. A sesame-seed flecked bun with just the right heft: substantial enough to be a meaningful component of the sandwich composition and to keep everything together until the last bite; but not so much as to overwhelm the stars of the show. It is just about perfect, and was the best thing I ate last week.

(You can see some more pictures in this La Pollita - Miami flickr set).

The mantra at EMP is "Make It Nice." The alumni running La Pollita learned it well.

La Pollita

2600 NE 2nd Avenue, Miami, Florida

310.435.7766

Thursday, April 13, 2017

A Very CSA Seder

Passover is something of a culinary challenge: the whole prohibition on leavened grains can be pretty limiting, especially when it comes to dessert, and there are certain things that are expected: the matzo ball soup, the gefilte fish, the brisket, the tzimmes. I wanted to be respectful of tradition without being completely straitjacketed by it – let’s be honest, some of those old-timey dishes are better than others (for further reading: Charlotte Druckman, “Can You Update a Passover Menu and Still Satisfy Traditionalists?,” which was a source of much of the inspiration for my menu, though not any of the actual dishes). Also, I had a stockpile of CSA vegetables gathering in the refrigerator bin, and at least one vegetarian joining us for dinner.

So here’s what I came up with, and where applicable, where my recipes came from, with a few I made up myself:

(You can see all my pictures in this Passover Home Cooking flickr set).

To Nosh:

Beet Pickled Eggs - you’ll find a multitude of recipes for these online and elsewhere - my starting point was this Michael Solomonov recipe. I happened to already have a bunch of beet pickling liquid from some fairly ancient brined beets I made using the Bar Tartine recipe,[1] so I used that as my base, diluting it with some water, reinforcing it with some white vinegar, and sweetening it with some sugar. I stuffed a dozen cooled, peeled hard-boiled eggs into a couple big jars and covered them with the beet liquid, then let them sit for two days in the fridge.

I was expecting our crowd to be skeptical of these – actually, I thought I'd be eating leftover pink egg salad sandwiches for the next week – but they were a big hit. The colors – sunny yellow yolk bordered by a ribbon of white fading into magenta exterior – are really striking, and the flavor has just enough pickle-y kick to let you know it’s there without being overwhelming. These are super easy, beautiful, and a crowd-pleaser.

Chopped Liver - when I was growing up, my grandmother – and then my mom – used to serve chopped chicken liver molded into the shape of a bird. Then everyone stopped eating chopped liver, which came to be regarded as deadly. I think it may be getting a bad rap. Yes, chicken livers, like many organ meats, are high in cholesterol, but they’re relatively low in fat and high in nutrients. Yes, you add some schmaltz, but you don’t need a ton. I followed this recipe from Russ & Daughters, subbing duck fat for chicken schmaltz because we were saving our schmaltz for the matzo balls. It says the yield is 8-10 servings, but you can probably comfortably serve this much to a group of twelve because there's going to be four people who don't eat liver. Besides, because it’s so rich and intense, you don’t need to eat all that much – just a couple shmears on some matzo, and you’ll be happy and fortified. I say “Bring Back Chopped Liver!”

Smoked Mackerel Dip - Unlike some people, I actually like gefilte fish, but sorry, I’m not going to make it from scratch. We happened to have some smoked mackerel fillets in a drawer of the fridge, so I figured - why not make a fish dip instead? I only stumbled across Felicity Cloake’s “How to Make the Perfect …” column in The Guardian by googling “smoked mackerel dip,” but appreciated the trial-and-error methodology of trying out multiple recipes and taking the best of each of them. It turned out quite nice, though I perked it up with supplemental additions of fresh horseradish, lemon and dill just before serving.[2]

Traditional:

Matzo Ball Soup - This was Mrs. F’s domain. I tried to pass along helpful tips via Serious Eats for getting your balls to be sinkers or floaters or somewhere in between, but she had no interest. I did well to just leave her alone. Her broth was golden and clear and deeply chicken-y; her matzo balls were just substantial enough to let you feel their presence, but light and fluffy rather than leaden.

Chicken Marbella - Here I thought I was some kind of genius for suggesting we do Chicken Marbella for Passover dinner. Turns out that the Silver Palate Cookbook staple also has a long and well-established history on the Seder table.

Brisket - My mom makes the best brisket. Just saying. One day I'll pass along her secrets.

Not So Traditional:

Summer Squash Kugel - I’d accumulated an assortment of zucchini and summer squashes from CSA the past couple weeks, which nobody else in my family will eat. So I figured, I may as well unload them on my guests. But how? I hatched my plan: a kugel.

Kugels are usually stodgy, dense side dishes of potato or noodles bound with egg. The traditional style is pretty heavy and, let's be honest here, pretty bland. But maybe they didn’t have to be that way. Via the almighty google, I found inspiration in this Spring Zucchini Kugel recipe. The result was exactly what I was looking for: lots of layers of vegetables, bound but not weighted down by the eggs – almost like a very veg-intensive frittata or strata. And the lemon zest and mint really brighten up the flavors. Here’s how I did it:

Recipe:

4 lbs zucchini, summer squash or both

2 tbsp olive oil

4 eggs

½ cup matzo meal

1 tbsp lemon zest

2 tbsp mint, chiffonade

Salt and pepper to taste

Preheat oven to 400°.

Thinly slice the squash crosswise (a mandolin might be too thin, you want them to have just a little substance), toss in a large bowl with 1 tbsp olive oil and salt, and then lay out in a single layer on a sheet pan and roast at 400° for about 5-10 minutes. I didn't want to brown them so much as just to soften them and get some of the liquid out. You might need to use multiple sheet pans or do them in batches; a Silpat comes in handy. Remove to a colander and let them drain any additional moisture.

Reduce oven to 350°.

Crack the eggs into a large mixing bowl and stir until the white and yolk are blended. Add the cooked squash, sprinkle in ½ cup matzo meal, lemon zest, mint, and a good pinch of salt, and gently stir to blend (hands probably work best).

Coat the bottom and sides of a baking dish with the remaining olive oil, then gently dump the contents of the mixing bowl into the baking dish. Try to arrange the squash slices so they are laying flat rather than pointing up (most seem to settle into the right position on their own, and in any event, precision is not essential).

Bake at 350° for about 45-60 minutes, until browned on top and cooked through. Can be made in advance and reheated.

Kohlrabi Anna - Kohlrabi is arguably an even bigger CSA challenge than a load of zucchini. I actually love the odd vegetable, which looks kind of like an alien turnip, and tastes a lot like broccoli stems, but it can be a tough sell. I had an idea: Kohlrabi Anna. The classic Potatoes Anna involves thinly sliced potatoes layered with lots of butter and cooked in a pan until the outer surface is browned and crisp, and the potatoes are tender. I basically did the same thing, but with kohlrabi. I would have liked to have gotten a little more browning – I may have been too timid with the heat – but I really liked how this came out, the kohlrabi tender and nutty and sweet and suffused with butter. This also can be made ahead and reheated though it may lose whatever crunch it may have had.

Recipe:

4 kohlrabi

3 tbsp unsalted butter

2 tbsp fresh thyme

Salt

Preheat oven to 375°.

Peel and thinly slice the kohlrabi into rounds.

Melt 1 tbsp of butter and toss the kohlrabi with the butter, salt and 1 tbsp of thyme.

Rub bottom and sides of a 10" cast iron skillet with 1 tbsp butter.

Arrange kohlrabi slices in circles around the bottom of the skillet, shingling them and overlapping the edges. Dot each layer with butter, sprinkle with salt, and continue layering kohlrabi slices until they're all used up.

Put the skillet on a medium-high heat burner on the stove for 10-20 minutes to brown the bottom. Then move skillet to the oven and cook for another 30-40 minutes, until kohlrabi are tender.

Remove from oven, and when feeling sufficiently bold, put a plate or cutting board over the top of the skillet, then flip the plate/cutting board and skillet – the kohlrabi should come out in one piece, like a cake.[3] Garnish with more fresh thyme, cut into wedges, and serve.

Roasted Carrots with Za’atar and Green Harissa Aioli - Charlotte Druckman is right: tsimis is totally broken. Tsimis, or tzimmes, or tsimmes, no matter how you spell it, is usually pretty gross – an insipid, cloyingly sweet stew of carrots and dried fruit, often supplemented with other sugary vegetables like yams. There's no contrast in flavor (just sort of generically sweet) or texture (just sort of generically soft). I don't think anyone actually likes tzimmes.[4] I was not going to make a tzimmes.

Instead, I took a few different varieties of CSA carrots, halved the fat ones, tossed with some olive oil and salt, and roasted them (400° for about 20-30 minutes, until the biggest ones were just barely fork tender), then sprinkled them with za'atar spice, and served them with a green harissa aioli.

My inspiration came from the fact that dessert involved a meringue, and I had a whole bunch of egg yolks left over.[5] I saved one of them for a favorite kitchen trick: immersion blender aioli. The recipe I've linked to is on Serious Eats, but the first time I saw this done, it was by José Andrés. Kenji uses the stick blender for half the oil (the canola portion), and then blends the olive oil in by hand. This seems unnecessary to me – I dumped it in all at once, and it came out just lovely. For some real excitement, make it right in a jam jar that's barely large enough for all the ingredients. If you start with the immersion blender at the bottom of the jar, and slowly, gently move your way up, it perfectly emulsifies all the oil without any splatters, and no need to decant into another container.

Once the aioli is made, just stir in prepared green harissa – or any other flavoring you like – to taste. I used a couple tablespoons of this Mina Green Harissa, which I like quite a bit. I also cut back to just three garlic cloves in the aioli recipe, as I didn't want the garlic to be dominant. Not to set the bar too low, but this was better than tzimmes.

Bitter Greens with Horseradish Ranch - the traditional Seder plate includes bitter herbs – maror and chazeret – for which we now customarily use horseradish and romaine lettuce, respectively. I started thinking about how I could incorporate these flavors into a dish, and while staring at the latest bag of lettuces from my CSA, decided on a bitter greens salad with horseradish ranch dressing. Crunchy, peppery fresh radishes also seemed thematically appropriate. This is my go-to formula for a creamy salad dressing, which welcomes all manner of variations – different herbs, finely chopped chile peppers, a dash of hot sauce, some mashed avocado. No doubt it's a common formula, but I think I arrived at it by way of Andrew Carmellini's buttermilk dressing recipe in "American Flavor."

Recipe:

2 tbsp white wine vinegar

2 tbsp grated fresh horseradish

2 garlic cloves, minced

½ cup buttermilk

½ cup plain Greek yogurt

½ cup mayonnaise

2 tbsp Fresh dill, chopped

Juice of 1 lemon

Salt, to taste

1 big bag mixed salad greens, washed and dried

1 watermelon radish, thinly sliced

3 breakfast radishes, thinly sliced

3 hakurei turnips, thinly sliced

Add vinegar to mixing bowl. Add horseradish and garlic and steep for 5-30 minutes. Add buttermilk, yogurt, mayo, dill and stir until combined. Add lemon juice and salt to taste. Add radishes and turnips to salad greens,[6] and toss with dressing.

Dessert:

Walnut Chocolate Dacquoise - I am not a baker. Dessert is generally the least exciting part of a meal for me, and I'm even less enthusiastic about making them. But I've been watching lots of Great British Baking Show on Netflix lately, and it's boosted my confidence a bit. And besides, Passover desserts are already pretty terrible (no leavened flour), so how badly could I do?

For whatever reason, meringue is a little easier for me to wrap my head around than most desserts, so I settled on this variation on a dacquoise. We had a big bag of walnuts in the house, and Mrs. F likes walnuts, so I substituted them for the hazelnuts. It was actually pretty easy: toast and chop the nuts, whip the egg whites to soft peaks, add sugar and whip to stiff peaks, mix in vanilla and almond extracts, then fold in the chopped nuts, chocolate chips, and melted chocolate. Then you spread the mixture out into three circles on parchment paper[7] – as far as I'm concerned, they don't need to look perfect – and bake at 225° for 2 1/2 hours, then let them cool and dry out in the oven.

When you're ready for assembly, whip three cups of heavy cream with 1/4 cup confectioner's sugar until you have whipped cream; then spread a layer of whipped cream over one of the meringues, top with a second meringue, repeat, top with the third meringue, and repeat once more. I then stuck it in the freezer overnight, sliced it straight out of the freezer (some bits will break off; save the crumbs), then moved it to the fridge the morning of Seder dinner. Before serving, I sprinkled the top with chocolate shavings, crumbled toasted walnuts, and the pulverized crumbles of meringue that had broken off during slicing.

Folks: it was ridiculously good. The meringue was maybe a bit dense, but it had a good crunch and crumble, the flavor of the walnut and chocolate carried through, the whipped cream was an airy, fluffy contrast, and even if it kind of looks like it's falling apart around the edges, it sliced very nicely to show the alternating layers of meringue and cream. I may be stuck with Passover dessert duty now.

Chocolate Toffee Matzo - this was a recipe I pulled from Bon Appetit, and accomplishes the unique feat of making matzo actually taste good (though of course it's not the matzo, its' everything you put on top of it). The idea is you make a toffee from butter and sugar (with a pinch of Aleppo pepper), spread that on the matzo, bake it for about 10 minutes, then melt chocolate over the top in the residual heat, spread the chocolate, and sprinkle with pistachios, coconut flakes, cocoa nibs, flaky salt, and more Aleppo pepper. Great flavors here; the toffee component left something to be desired – whether because the instructions are flawed (I don't think a "simmer" gets the toffee thick enough) or my own failed execution, the toffee wasn't spreadable, and wound up more like a soak in a hot, sweet melted butter bath for the matzo. Sticking it in the freezer after it was fully assembled and cooled helped it firm up.

So we got to share the holiday with family and friends, we got to tell the story of Passover one more time, we drank wine and reclined, we used up a whole bunch of our CSA produce, and we discovered I can actually make a dessert. That was the fun part. Now comes the hard part – not eating bread for a week. Chag Sameach to all my fellow tribespeople, and as for the rest of you: please stop posting pictures of delectable baked goods for the next week.

[1] Oh my gosh - could these have been the same pickled beets I wrote about making two years ago? Maybe.

[2] While this menu is "kosher for Passover," it is not actually "kosher" – we’ve got both meat and milk all over the place at the same time. Hey, we each observe in our own ways.

[3] When you pull it from the oven, give the skillet a little shake to make sure the kohlrabi isn't sticking (if it is, I'm not sure how to help you). If you flip it onto a cutting board (I find this easier than a dish because the cutting board is flat), you can then slide it from the cutting board onto a serving dish.

[4] This is a big part of why Chicken Marbella makes so much sense as part of a Seder: you can offload all that sweet stuff into a meat dish where you at least get some contrast from the olives and capers and herbs.

[5] Pro tip: with the rest of the yolks, make a lemon or other citrus curd (I had blood oranges, and used this recipe as a starting point, but used five yolks instead of the three yolks and three whole eggs called for in the recipe, and cut the sugar back to 1/4 cup); then dollop spoonfuls of the curd on macaroons.

[6] The radishes can be sliced the day before and kept in ice water, they'll remain nice and crisp and this makes last-minute assembly easier.

[7] I actually made a piping bag from a Ziploc with a corner cut off, but my piping was, well, pretty inartful (let's just say I was reminded of walking the dogs) and so I then spread it out into circles using an offset spatula.

[2] While this menu is "kosher for Passover," it is not actually "kosher" – we’ve got both meat and milk all over the place at the same time. Hey, we each observe in our own ways.

[3] When you pull it from the oven, give the skillet a little shake to make sure the kohlrabi isn't sticking (if it is, I'm not sure how to help you). If you flip it onto a cutting board (I find this easier than a dish because the cutting board is flat), you can then slide it from the cutting board onto a serving dish.

[4] This is a big part of why Chicken Marbella makes so much sense as part of a Seder: you can offload all that sweet stuff into a meat dish where you at least get some contrast from the olives and capers and herbs.

[5] Pro tip: with the rest of the yolks, make a lemon or other citrus curd (I had blood oranges, and used this recipe as a starting point, but used five yolks instead of the three yolks and three whole eggs called for in the recipe, and cut the sugar back to 1/4 cup); then dollop spoonfuls of the curd on macaroons.

[6] The radishes can be sliced the day before and kept in ice water, they'll remain nice and crisp and this makes last-minute assembly easier.

[7] I actually made a piping bag from a Ziploc with a corner cut off, but my piping was, well, pretty inartful (let's just say I was reminded of walking the dogs) and so I then spread it out into circles using an offset spatula.

Monday, April 3, 2017

Rules Restaurant | London

Fergus Henderson may have helped convince the world that British food was worthy of attention with his restaurant, St. John (some more thoughts on St. John here). But at Rules, they were never in any doubt.

Rules bills itself as the oldest restaurant in London. Over the past two centuries, it's been owned by only three families: Thomas Rule opened it in 1798; just before World War I, one of his descendants decided to move to France, and arranged a swap with a Brit running a restaurant in Paris named Tom Bell; and then in 1984, Bell's daughter sold the restaurant to its current owner John Mayhew.

The dining room, with its red velvet-wrapped, gold-piped banquettes, polished wood dividers, oil portraits and old cartoons on the walls,[1] the occasional marble bust here and there, looks every bit the part. If not for the bona fides of its history, the stereotypically posh decorations would seem almost laughable. I adore the place.

We first came here on a family trip to London more than ten years ago. Our daughter was about six years old at the time; she did not adjust well to the jet lag, and within an hour she was sliding under the table.[2] This time around, I was the one who wanted to throw a fit when I learned that we had just missed game season. Through the present owner's inheritance of the Lartington Estate in northern England and relationships with local game dealers, Rules sometimes has a glorious assortment of wild things on the menu – its "famous grouse," but also woodcock, pheasant, partridge, wild duck, hare and more. Alas, not on this visit.

(You can see all my pictures in this Rules - London flickr set).

Before getting to the food, I highly recommend a visit upstairs to the Edward VII Room, a/k/a the cocktail bar, a snug spot with a carved wooden bar counter, a few tables and couches, and a fine assortment of hunting murals and trophies adorning the walls. The bar program is run by Mike Cook, and his crew can handily make the classics like a pitch-perfect Negroni. But they also have their own creations, like the intensely aromatic Lucia Sciarra, named after a character from the last James Bond film, Spectre.[3]

Once I'd recovered from having missed game season (my recovery aided by a pleasant cocktail), I focused my attention on the menu, which also helped ease my disappointment. You get the sense it could have been written a hundred years ago. Chef David Stafford shows occasional flashes of whimsy, like a duck leg "pastilla" paired with a spiced duck breast, but for the most part he proudly and lovingly cooks traditional British dishes. And this he does exceedingly well.

So there's potted shrimps, a mound of tiny, tender brown crustaceans caught in Morecambe Bay, preserved in butter and spices in the way it's been done for hundreds of years. There's Middlewhite pork terrine, which makes use of a rare heritage breed of pig that originated in Yorkshire, served simply with picallili and cornichons. The shrimp taste of shrimp, the pork tastes of pork, and I couldn't possibly be happier.

For her main, Mrs. F chooses the Uig Lodge smoked salmon, sourced from a smokery on the far northern reaches of the Outer Hebrides. The salmon is served with fat slabs of brown bread and offered either with or without scrambled eggs, but surely this is a rhetorical question? The salt and smoke on the fish whisper rather than shout, and its texture is all silk, matched by the soft, creamy eggs.

For me, a real taste of tradition: a steamed suet pudding. It arrives at the table completely unadorned, looking like a doorstop from a giant's castle. Cut it open, and beneath a layer of dense, chewy suet pastry, a stew of venison, red wine and chestnut mushrooms issues forth. There's nothing light or delicate here, but it has a brawny beauty all its own; it's rich, and hearty, and sticky, and satisfying, and I love that such things still exist in this world.

Along with our mains, we have some bronze-crested, buttery-interiored potatoes Anna, as well as a perky salad with sprightly pale sprigs of frisée, crispy bacon lardons, toasty croutons and a bracing shallot vinaigrette.[4]

We always enjoy ending a meal with some good cheeses, but Mrs. F is not so much a fan of the blue-veined varieties. So I'm pleased to hear that the cheese plate, which features a few English cheeses served with biscuits and a sweet shallot jam, can be supplemented with a portion of the Cropwell Bishop Stilton. The entire wheel is brought to the table, from which they will scoop the paste onto your plate until you say "enough!" Made by a third-generation creamery in Nottingham, it's more creamy than crumbly, tangy enough to balance the fat but not so much to blow out your sinuses, and just lovely stuff.

There's a certain danger in a place like this getting weighed down by its historical baggage, but Rules manages to avoid that. It doesn't feel, or taste, like a museum piece, but rather like a living, breathing restaurant that just happens to be from another century. But good food is timeless; I hope Rules remains so as well.

Rules Restaurant

35 Maiden Lane, Covent Garden, London, England

+44 0 20 7836 5314

[1] There's also a massive mural on one wall of a stern-faced Margaret Thatcher looking as if she belongs on the prow of a ship.

[2] She didn't actively misbehave. She just sort of ran out of steam, started to fade and get a little teary-eyed, and quietly mewled "I'm broken." We still say this when it gets a little too late in the evening for any of us.

[3] The concoction includes Star of Bombay Gin, Lillet Blanc, Benedictine, Gammel Dansk Bitter Dram, and a lemon twist. You can see Cook making one here. Delicious. You can also see Rules make a cameo appearance in a scene from Spectre which was shot at the restaurant. Rules has made many other literary appearances, including in novels by Evelyn Waugh and Graham Greene, among others. Speaking of things literary, I think it's just wonderful that the restaurant proudly republishes an absolutely scathing review by Kingsley Amis entitled "Where Disaster Rules," written sometime in the 1970's, on their website ("There are cheaper eating-places than Rules where the atmosphere and service are so pleasant that they drive out other impressions. Far from the case here; but then I find it hard to imagine an establishment Elysian enough to dispel the memory of two of the most disgusting full-dress meals I have ever tried to eat in my life.")

[4] We also drink a really nice wine, the 2010 Rossignol-Fevrier "Robardelle," a premier cru vineyard in Volnay from a producer which I don't think gets distributed in the U.S. Happily, the wine list at Rules mostly shares my predilections for Burgundies, Rhones, and sub-$100 wines.

[2] She didn't actively misbehave. She just sort of ran out of steam, started to fade and get a little teary-eyed, and quietly mewled "I'm broken." We still say this when it gets a little too late in the evening for any of us.

[3] The concoction includes Star of Bombay Gin, Lillet Blanc, Benedictine, Gammel Dansk Bitter Dram, and a lemon twist. You can see Cook making one here. Delicious. You can also see Rules make a cameo appearance in a scene from Spectre which was shot at the restaurant. Rules has made many other literary appearances, including in novels by Evelyn Waugh and Graham Greene, among others. Speaking of things literary, I think it's just wonderful that the restaurant proudly republishes an absolutely scathing review by Kingsley Amis entitled "Where Disaster Rules," written sometime in the 1970's, on their website ("There are cheaper eating-places than Rules where the atmosphere and service are so pleasant that they drive out other impressions. Far from the case here; but then I find it hard to imagine an establishment Elysian enough to dispel the memory of two of the most disgusting full-dress meals I have ever tried to eat in my life.")

[4] We also drink a really nice wine, the 2010 Rossignol-Fevrier "Robardelle," a premier cru vineyard in Volnay from a producer which I don't think gets distributed in the U.S. Happily, the wine list at Rules mostly shares my predilections for Burgundies, Rhones, and sub-$100 wines.

Saturday, April 1, 2017

St. John Bread and Wine | London

Until recently, British food has been saddled with a terrible reputation. I'm reminded of the old George Carlin joke about heaven and hell:

"In heaven, the Italians are the lovers, the French cook the food, the Swiss run the hotels, the Germans are the mechanics, and the English are the police. In hell, the Swiss are the lovers, the English cook the food, the French run the hotels, the Italians are the mechanics, and the Germans are the police."

That reputation, I've always thought, has been undeserved. Even thirty years ago, when I spent a summer in Oxford "studying," I ate very well. Ploughman's lunches with good cheese and bread, rich steak and kidney pies, crisp, steamy fish and chips wrapped in newspaper, fiery Indian and Jamaican food – what's not to like?

Over the past couple decades, general sentiment seems to have shifted, and now London is regarded as one of the world's top dining destinations. Partly that's been driven by international attention for this very moneyed, lucrative market; one of the odd things about planning a recent brief visit to both London and Paris (three days in each) was realizing that many of Paris' top chefs have opened outlets in London so that, in Epcot-like fashion, you could arguably taste some of the best of Paris without ever crossing the Channel. But even more so, it's been driven by English chefs' internal reflection: recognizing, and promoting, great British cookery.

One of the individuals who was formative in that shift was Fergus Henderson. His restaurant, St. John, which opened in 1995, and his cookbook, first published in 1999 as "Nose to Tail Eating: A Kind of British Cooking" (released in the U.S. in 2004 as "The Whole Beast: Nose to Tail Eating") are mostly recognized for being a manifesto on the joys of offal and whole-animal utilization. They are most definitely that, but they also are an ode to traditional British dishes – things like cock-a-leekie soup and bath chaps and game birds and Eccles cakes – and the value of native ingredients.

I'd never been. So it was the first dinner reservation I made for this trip.

We actually booked at St. John Bread and Wine, a sibling to the original St. John around the corner from Smithfield Market. Bread and Wine, originally intended to be a bakery and wine shop (thus the name), makes its home across from the Spitalfields Market,[1] and is slightly more casual than the mothership. More of the menu is offered as small plates, and they ascribe to the "dishes come out as they're ready and are meant for sharing" school of service. Since this gave us an opportunity to sample broadly, it was perfect.

(You can see all my pictures in this St. John Bread and Wine flickr set).

Of course, you have to start with the roasted marrow bones – Henderson's most famous dish, one that has been lovingly duplicated countless times in countless restaurants around the world, one that Anthony Bourdain declared his "always and forever choice" for his Death Row meal. The formula is now well-known: roasted femur bones; toasted bread; a pile of parsley salad; a mound of coarse sea salt. Scoop the oozy marrow from the bone, spread on to the toast, dress with a sprinkle of salt and a pinch of the salad, and enjoy. I've had it dozens of times, but never until now the original. And yes, it's the best: the marrow at the magic borderline between solid and liquid, the acid and salt and herbaceous bite of the salad right on the edge of too aggressive without crossing the line, with just the right punch of caper and shallot. I can't say it better than Fergus himself:

"Do you recall eating Raisin Bran for breakfast? The raisin-to-bran-flake ratio was always a huge anxiety, to a point, sometimes, that one was tempted to add extra raisins, which inevitably resulted in too many raisins, and one lost that pleasure of discovering the occasional sweet chewiness in contrast to the branny crunch. When administering such things as capers, it is very good to remember Raisin Bran."Though not as famous, the other dishes we tried exhibited the same winning combination of good, honest ingredients, intense, robust flavors, and attentive execution.

I loved these tender curls of lamb's tongues wrapped around cubes of bread, all enrobed in a bright, verdant green sauce, like a meaty panzanella salad. Picking at a smoked fish nearly always brings me joy, and the minimalist approach here – the unadorned back end of a smoked mackerel, served simply on a plate with a potato salad given a sinus-clearing blast of mustard dressing – is my kind of happy meal.

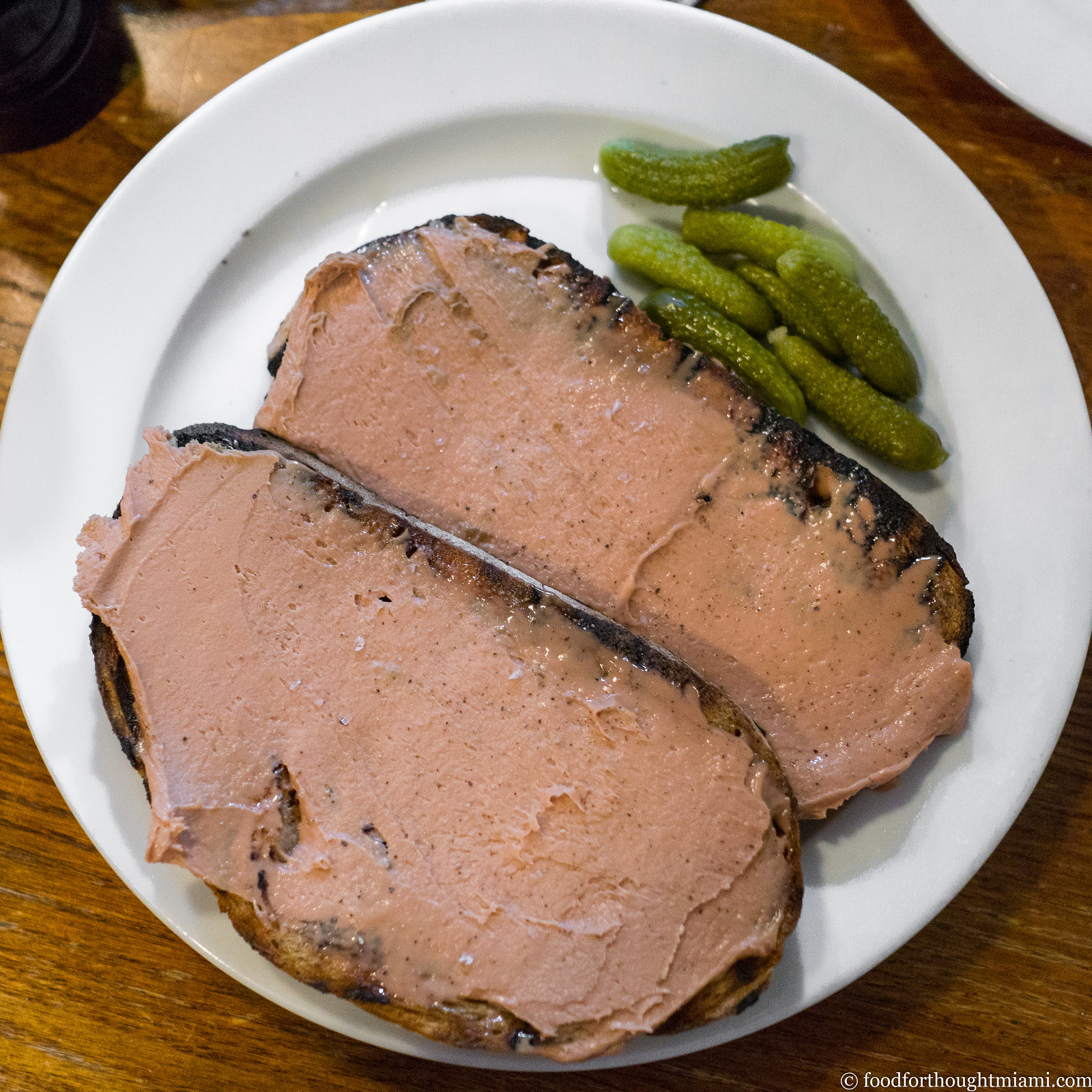

Another testament to the joy of simplicity: slabs of toast spackled with a rich, intense mousse of duck livers and foie gras. It's just nearly too much; then you take a bite of cornichon, your appetite is restored, and you go back for more. The smoked cod's roe is like salt, smoke and sea wrapped in silk, but maybe the best part are the crispy batons fashioned from thin layers of potato perched on top. We finished with deviled kidneys: chewy, soft, springy, and ferrous, served over toast drenched with cooking juices spiked with mustard powder and Worcestershire sauce.[2]

We ordered dessert whilst draining the last of a bottle of Beaujolais, starting first with St. John's version of a classic – Eccles cake. There are whole families of traditional British desserts of which I know nothing, this being a good example. Every time I'd peruse the online menu at St. John I'd see it, and so of course I had to order it. The sweetness of the "cake" – a flaky pastry wrapped around a filling of sticky currants – is balanced by an accompanying slab of fresh, crumbly, sharp, faintly salty Lancashire cheese. Then a few minutes later, a batch of warm, airy madeleines, fresh from the oven. We trusted our server for something to drink with these, and our trust was rewarded with a glass of Pineau de Charentes.

Honestly, I wondered if St. John would live up to its nearly mythical reputation. Bourdain, in his foreword to the U.S. release of Nose to Tail, acknowledges, "My enthusiastic rant in my book A Cook's Tour made him sound like George Washington, Ho Chi Minh, Lord Nelson, Orson Welles, Pablo Picasso, and Abbie Hoffman – all rolled into one." And Henderson, both in interviews and on the page, evinces such unbridled enthusiasm, humble charm, and subtle wit that it's hard to imagine not liking his food. This is a man who can make curly parsley sound good![3]

But this was just a joyous meal: great ingredients; straightforward, bold, intense flavors; presented without any fanfare but prepared with subtle finesse. In my version of heaven, Fergus is welcome to cook the food.

St. John Bread and Wine

94-96 Commercial Street, London

020 7251 0848

[1] While Smithfield is still a functioning meat market, Spitalfields has been refurbished into a shopping mall.

[2] I rarely get to eat kidneys, and even more rarely get to eat properly prepared kidneys, but even so, their sort of crumbly, bouncy texture still puts them fairly low on my Favorite Offal list. Tripe, or livers, or sweetbreads, or hearts, would all rank before kidneys in my book.

[3] "As the swish, swish, swish of bunches of flat Italian parsley is to be heard in kitchens across the land, it seems time to celebrate the strength and character of the indigenous curly parsley. Its expression of chlorophyll and well being, strong flavor, slightly prickly texture, and its structural abilities enable such things as Parsley Sauce."

[2] I rarely get to eat kidneys, and even more rarely get to eat properly prepared kidneys, but even so, their sort of crumbly, bouncy texture still puts them fairly low on my Favorite Offal list. Tripe, or livers, or sweetbreads, or hearts, would all rank before kidneys in my book.

[3] "As the swish, swish, swish of bunches of flat Italian parsley is to be heard in kitchens across the land, it seems time to celebrate the strength and character of the indigenous curly parsley. Its expression of chlorophyll and well being, strong flavor, slightly prickly texture, and its structural abilities enable such things as Parsley Sauce."