Until recently, British food has been saddled with a terrible reputation. I'm reminded of the old George Carlin joke about heaven and hell:

"In heaven, the Italians are the lovers, the French cook the food, the Swiss run the hotels, the Germans are the mechanics, and the English are the police. In hell, the Swiss are the lovers, the English cook the food, the French run the hotels, the Italians are the mechanics, and the Germans are the police."

That reputation, I've always thought, has been undeserved. Even thirty years ago, when I spent a summer in Oxford "studying," I ate very well. Ploughman's lunches with good cheese and bread, rich steak and kidney pies, crisp, steamy fish and chips wrapped in newspaper, fiery Indian and Jamaican food – what's not to like?

Over the past couple decades, general sentiment seems to have shifted, and now London is regarded as one of the world's top dining destinations. Partly that's been driven by international attention for this very moneyed, lucrative market; one of the odd things about planning a recent brief visit to both London and Paris (three days in each) was realizing that many of Paris' top chefs have opened outlets in London so that, in Epcot-like fashion, you could arguably taste some of the best of Paris without ever crossing the Channel. But even more so, it's been driven by English chefs' internal reflection: recognizing, and promoting, great British cookery.

One of the individuals who was formative in that shift was Fergus Henderson. His restaurant,

St. John, which opened in 1995, and his cookbook, first published in 1999 as "Nose to Tail Eating: A Kind of British Cooking" (released in the U.S. in 2004 as "

The Whole Beast: Nose to Tail Eating") are mostly recognized for being a manifesto on the joys of offal and whole-animal utilization. They are most definitely that, but they also are an ode to traditional British dishes – things like cock-a-leekie soup and bath chaps and game birds and Eccles cakes – and the value of native ingredients.

I'd never been. So it was the first dinner reservation I made for this trip.

We actually booked at

St. John Bread and Wine, a sibling to the original

St. John around the corner from

Smithfield Market. Bread and Wine, originally intended to be a bakery and wine shop (thus the name), makes its home across from the

Spitalfields Market,

[1] and is slightly more casual than the mothership. More of the menu is offered as small plates, and they ascribe to the "dishes come out as they're ready and are meant for sharing" school of service. Since this gave us an opportunity to sample broadly, it was perfect.

(You can see all my pictures in this

St. John Bread and Wine flickr set).

Of course, you have to start with the roasted marrow bones – Henderson's most famous dish, one that has been lovingly duplicated countless times in countless restaurants around the world, one that Anthony Bourdain declared his "always and forever choice" for his Death Row meal. The formula is now well-known: roasted femur bones; toasted bread; a pile of parsley salad; a mound of coarse sea salt. Scoop the oozy marrow from the bone, spread on to the toast, dress with a sprinkle of salt and a pinch of the salad, and enjoy. I've had it dozens of times, but never until now the original. And yes, it's the best: the marrow at the magic borderline between solid and liquid, the acid and salt and herbaceous bite of the salad right on the edge of too aggressive without crossing the line, with just the right punch of caper and shallot. I can't say it better than Fergus himself:

"Do you recall eating Raisin Bran for breakfast? The raisin-to-bran-flake ratio was always a huge anxiety, to a point, sometimes, that one was tempted to add extra raisins, which inevitably resulted in too many raisins, and one lost that pleasure of discovering the occasional sweet chewiness in contrast to the branny crunch. When administering such things as capers, it is very good to remember Raisin Bran."

Though not as famous, the other dishes we tried exhibited the same winning combination of good, honest ingredients, intense, robust flavors, and attentive execution.

I loved these tender curls of lamb's tongues wrapped around cubes of bread, all enrobed in a bright, verdant green sauce, like a meaty panzanella salad. Picking at a smoked fish nearly always brings me joy, and the minimalist approach here – the unadorned back end of a smoked mackerel, served simply on a plate with a potato salad given a sinus-clearing blast of mustard dressing – is my kind of happy meal.

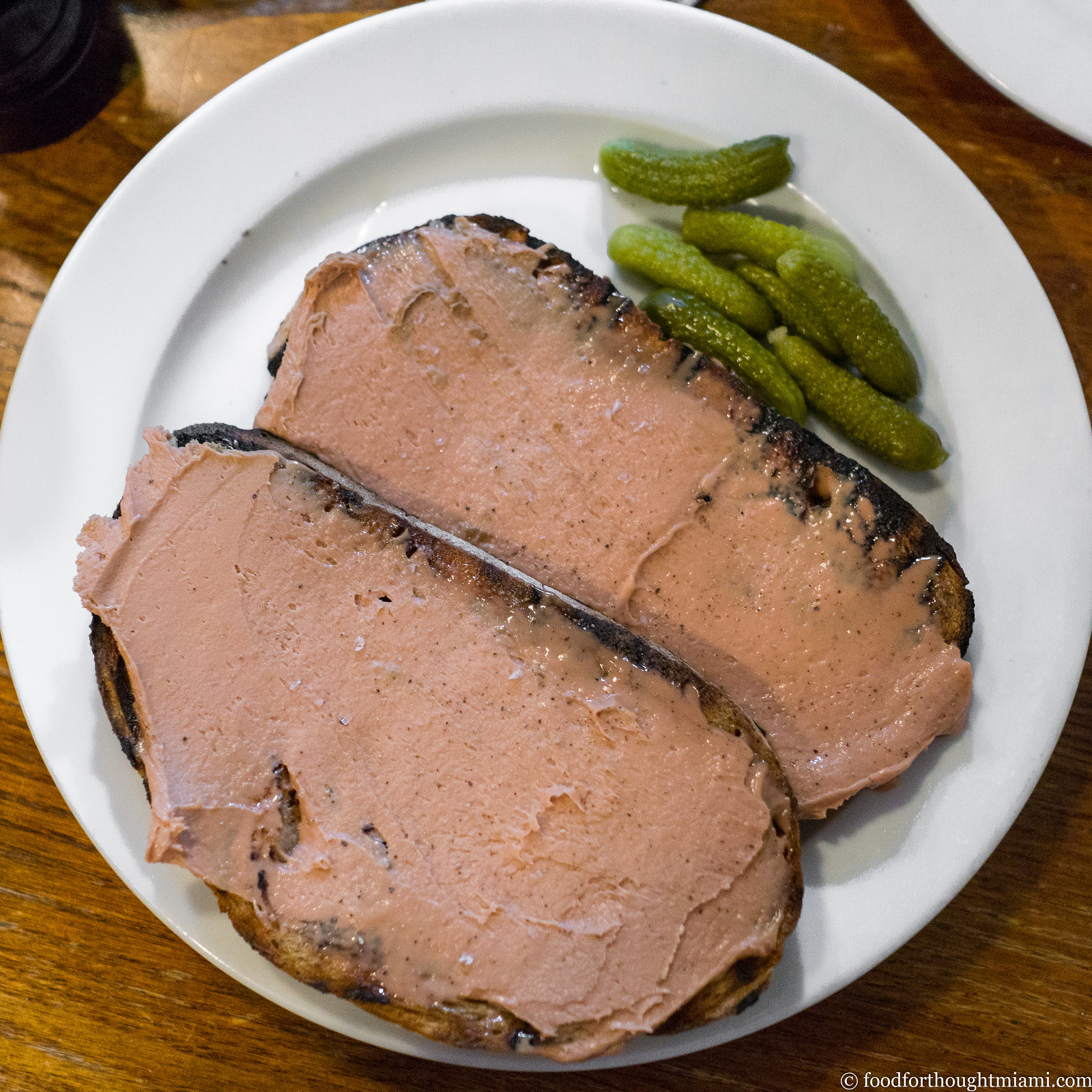

Another testament to the joy of simplicity: slabs of toast spackled with a rich, intense mousse of duck livers and foie gras. It's just nearly too much; then you take a bite of cornichon, your appetite is restored, and you go back for more. The smoked cod's roe is like salt, smoke and sea wrapped in silk, but maybe the best part are the crispy batons fashioned from thin layers of potato perched on top. We finished with deviled kidneys: chewy, soft, springy, and ferrous, served over toast drenched with cooking juices spiked with mustard powder and Worcestershire sauce.

[2]

We ordered dessert whilst draining the last of a bottle of Beaujolais, starting first with St. John's version of a classic – Eccles cake. There are whole families of traditional British desserts of which I know nothing, this being a good example. Every time I'd peruse the online menu at St. John I'd see it, and so of course I had to order it. The sweetness of the "cake" – a flaky pastry wrapped around a filling of sticky currants – is balanced by an accompanying slab of fresh, crumbly, sharp, faintly salty Lancashire cheese. Then a few minutes later, a batch of warm, airy madeleines, fresh from the oven. We trusted our server for something to drink with these, and our trust was rewarded with a glass of Pineau de Charentes.

Honestly, I wondered if St. John would live up to its nearly mythical reputation. Bourdain, in his foreword to the U.S. release of Nose to Tail, acknowledges, "My enthusiastic rant in my book

A Cook's Tour made him sound like George Washington, Ho Chi Minh, Lord Nelson, Orson Welles, Pablo Picasso, and Abbie Hoffman – all rolled into one." And Henderson, both in interviews and on the page, evinces such unbridled enthusiasm, humble charm, and subtle wit that it's hard to imagine

not liking his food. This is a man who can make curly parsley sound good!

[3]

But this was just a joyous meal: great ingredients; straightforward, bold, intense flavors; presented without any fanfare but prepared with subtle finesse. In my version of heaven, Fergus is welcome to cook the food.

St. John Bread and Wine

94-96 Commercial Street, London

020 7251 0848