Showing posts with label modern gastronomy. Show all posts

Showing posts with label modern gastronomy. Show all posts

Wednesday, October 18, 2017

é by José Andrés | Las Vegas

There's a phenomenon on social media lately that whenever a celebrity chef expresses an opinion on political or social issues, a chorus of those whose sensibilities diverge insist that the chef should "stay in their lane." In other words, talk about food all you want, but keep your politics to yourself. The reaction seems inherently ridiculous to me – if you don't like it, the "unfollow" button is a simple, elegant solution – and hypocritical. Unless, that is, all these "stay in your lane" folks are actually career political scientists themselves, or perhaps professional life coaches.

I bring this up here because Chef José Andrés is a powerful retort to that kind of nonsense, someone whose talk has been backed up by meaningful, thoughtful action. The day after Hurricane Harvey cleared Texas, he was in Houston feeding people. A month later when Hurricane Maria decimated Puerto Rico, he was there within days serving meals. Over the past weeks, he's mobilized a brigade of food trucks and canteen kitchens to serve 100,000 meals a day, while getting minimal support from the federal government, in a territory with an almost entirely broken infrastructure.[1]

But this shouldn't come as a surprise. His charity work is not simply a reaction to recent events, but a commitment that dates back to at least 2010, when he founded a non-profit, World Central Kitchen, as a response to a devastating earthquake in Haiti. When, in mid-2016, then-candidate Trump described Mexicans as criminals and rapists, Andrés – an immigrant and naturalized U.S. citizen himself – didn't just gripe about it on Twitter. He pulled out of a multi-million dollar restaurant deal at a Trump property in DC, risking the inevitable lawsuit from the litigation-happy candidate. (Andrés countersued, and the case settled in April on undisclosed terms.)

All of which is to say: José Andrés can cruise in any lane he wants, as far as I'm concerned.

While the work he's doing now in Puerto Rico is infinitely more important, those lanes do actually include chef and restaurateur as well. Andrés' restaurants include the Michelin two-star Minibar, along with a mini-empire of places in DC, LA, Miami, and Las Vegas, the last of which I visited recently for a conference.[2] While there, I squeezed in a dinner at é by José Andrés, an 8-seat "restaurant within a restaurant" inside Jaleo at the Cosmopolitan.

(You can see all my pictures in this é by José Andrés - Las Vegas flickr set).

The format of é is patterned after the original iteration of Minibar in DC with a dollop of Vegas glitz. Its roughly 20-course tasting menu is unabashedly inspired by the creations of Andrés' mentor, Ferran Adrià, with whom Andrés worked at El Bulli in Spain before going on to tremendous success in the U.S. I'd visited é once before, though I hadn't realized how long ago it had been – nearly six years. The room, centered by a polished metal chef's counter surrounded by walls lined with tiny drawers and odd tchotchkes, hasn't changed much. One of the chefs said it was meant to make you feel like "You're inside Chef Andrés' head." (It kind of does.) The menu was almost entirely different, though there were some echoes of prior meals.

Guests are corralled at a table in Jaleo and offered a drink before the dinner at é starts. After a few minutes, the hostess divulges that the centerpiece on the table is also the first course: a cracker flavored with black olive, stuck with edible flowers.

Then upon entering the cloistered dining room, a cocktail: sangria, frozen and powdered to a slushie-like consistency, with compressed melon, sour cherry pearls, and fresh mint leaves.[3]

A cheese course of sorts: a soft-frozen manchego and beet rose topping a walnut cracker, "stones" of idiazabal cheese with a jamón and rosemary glaze nestled atop a bowl of river stones; and a "pizza" of San Simon cheese topped with oregano cream, dried tomato, and fresh shaved truffle.

(continued ...)

Monday, January 16, 2017

Cobaya DK with David Lanster and Kelly Moran

When we first started doing these Cobaya dinners, we saw it as, among other things, an opportunity to give fledgling young chefs an opportunity to test out their skills. So our most recent event, Experiment #68, felt something like a return to our roots: a small group (only 18 diners), a couple young chefs (only 19 years old!), outside of a restaurant (in a beautiful loft space overlooking the Biscayne Boulevard MiMo District, generously lent to us by Pietro Morelli, who also runs Made In Italy Gourmet in Wynwood).

The chefs were David Lanster and Kelly Moran, who first started doing "pop-up" dinners for family and friends when they were in high school to raise money for the Common Threads charity. They're now sophomores in college. To put that in perspective, when we first started doing these Cobaya dinners, David and Kelly were about eleven years old.

David's interests lie in the scientific aspects of cooking, while Kelly is the baker and pastry chef of the pair. But they're not diving into the culinary world with both feet quite yet: Kelly is studying at Tufts, while David is at University of Miami. So while DK Culinary Ventures is on something of a hiatus, David and Karen – with assistance from friends and former classmates – turned out an ambitious, fourteen-course dinner for us during their winter break.

(You can see all my pictures from the dinner in this Cobaya DK with David Lanster and Kelly Moran flickr set).

The meal started with a series of snacks: a "house salad" which used Ferran Adrià's spherification technique to suspend bits of tomato and carrot in an orb of lettuce juice, dressed with dashes of olive oil, balsamic vinegar and sea salt; savory pumpkin seed macarons sandwiching sautéed mushrooms, brie and celery leaves; a one-bite mojito cocktail assembled from a candied mint leaf flavored with citric acid and a rum gel; and savory, green-hued sunflower cakes topped with mandarin orange segments and chia seeds, visually mimicking their main ingredient.

A root vegetable antipasto salad was a beautiful presentation that made good use of vacuum compression, infusing each of the thinly sliced vegetables with a different flavor: the red beets with red wine, the golden beets with white wine, the parsnip with apple juice and ginger, the carrots with orange and caraway seed. They were then topped with a goat cheese gelato (yup, beets and goat cheese), and a crunchy rye bread crumble.

(continued ...)

Sunday, November 13, 2016

In Situ - San Francisco

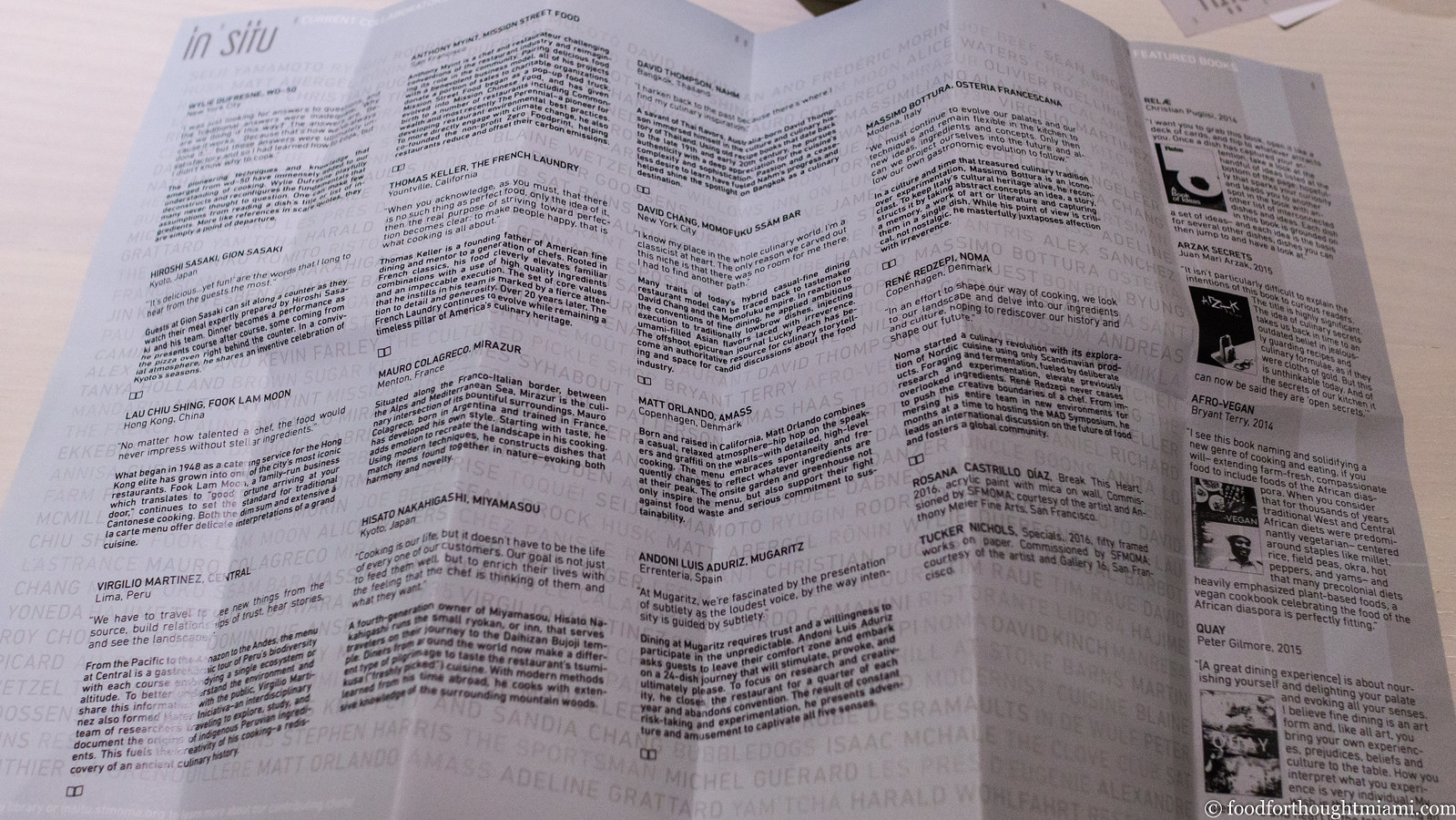

In Situ, the new restaurant in the recently refurbished and reopened San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, is a bundle of contradictions. The chef is Corey Lee, whose tasting-menu flagship, Benu, just retained the three Michelin stars it was first awarded in 2014. But the highly regarded chef didn't create a single recipe for the restaurant. Rather, the menu consists of a rotating selection of other chefs' dishes from all around the world, which the In Situ kitchen sets out to faithfully recreate. In other words, it's a restaurant in the model of an art exhibition, with Lee as the curator.

In this and other ways, including the exhibition catalog-style menu, In Situ clearly advances the notion of chef as artist. But the manner by which it is implemented – with Lee and his crew duplicating the "artists'" creations – undermines the very notions of authorship and uniqueness that are generally thought of as essential to the distinction between "art" and "craft." While Lee is ostensibly in the role of curator and not creator, the lines become blurred: when was the last time you saw a museum curator break out his brushes and hang up his own canvas on the museum wall as the "Mona Lisa"?[1] What you will get here is at best a copy, though it may be a very good one.

Indeed, the very name is a contradiction: "in situ" refers to a site-specific artwork, one that is created for the location. Yet each of the dishes served at In Situ was created for and is usually served in some other restaurant.

All of which is to say this: In Situ is possibly the most thought-provoking restaurant experience I've had in years. But unlike many restaurant experiences that aim to be thought-provoking, this one was also a lot of fun and mostly really delicious.

(You can see all my pictures in this In Situ - San Francisco flick set).

A big part of the fun at In Situ is that the restaurant acts as both Star Trek transporter and Dr. Who time travel TARDIS telephone booth. Here, in one meal, you can sample dishes from thousands of miles away, and even from decades past – some of which may no longer even be available anywhere else.[2]

For instance, the lead-off item on the menu[3] during our visit comes from chef Wylie Dufresne. His restaurant in New York's Lower East Side, wd~50, was a mid-aughts "molecular gastronomy"[4] trendsetter. But I never managed to get there before it closed in 2014.

Yet here are Dufresne's "shrimp grits," a dish which subverts the classic Southern pairing, turning the shrimp themselves into the grits by chopping, cooking, finely grinding, and finally re-warming them with powdered freeze-dried corn, then garnishing with pickled jalapeños and a bright orange shrimp shell oil.

If I'm to be honest, one of the reasons I never ate at wd~50 is that I wasn't convinced I would have enjoyed an entire meal there: the place often gave me the impression that form was being elevated over substance, creativity over flavor. But that's another of the interesting things about In Situ: it's a chance to sample a chef's cooking (at least vicariously through the medium of Lee and crew), without the commitment of a full meal. Turns out, this dish was excellent: intense crustacean flavor, combined with a nostalgic creamy, nubby grits texture. Perhaps I misjudged. But In Situ offers a taste of what I missed.

We were in Kyoto a couple years ago, but did not go to Gion Sasaki, a kaiseki style restaurant that is a notoriously difficult reservation. So here is another "missed opportunity" dish. Tender, meaty chicken thighs are glazed with a delicate teriyaki sauce (not the gloppy syrupy stuff we get here, but a fine calibration of salty, tangy and sweet); concealed beneath them is a wobbly "onsen" egg (probably cooked in an immersion circulator rather than the traditional hot spring), mounted in a bed of crunchy lettuce, and dusted with tingly sansho pepper. It's Sasaki's version of "oyako," i.e. "parent and child" (chicken and egg), and it's superficially simple but elegantly balanced.

One of the challenges In Situ faces is finding dishes that can be replicated without access to all of the ingredients used by chefs whose restaurants may be thousands of miles away. Virgilio Martinez's cooking at Central in Lima, Peru is indelibly tied to indigenous products, many of which are found nowhere else in the world. So when he chose a dish for the In Situ menu, he had to do something that would "travel well." (More interesting tidbits in this conversation between Martinez and Lee captured by Lucky Peach).

His "Octopus and the Coral" is the result: plump octopus tentacles basted in a spicy rocoto chile paste, hidden beneath shards of silver savory meringues, dark grey rice crackers, and tufts of red seaweed, meant to appear like an octopus crouching within a coral-covered rock beneath the sea. It was a good dish, though not nearly as interesting as several dishes Martinez prepared for a dinner at Alter restaurant in Miami earlier this year.

(continued ...)

Thursday, October 6, 2016

Boragó | Santiago, Chile

As I mentioned in Part 1 of my Chile travelogue, before we'd decided to visit Chile, I knew very little about the country's food. In fact, there was only one restaurant I could name: Boragó. Boragó's chef, Rodolfo Guzman, opened the restaurant in 2007 after taking an interesting path into the kitchen: he studied chemical engineering, went to culinary school when a broken ankle ended a career as a professional water-skier, then spent time working at Andoni Luis Aduriz's restaurant Mugaritz in Spain's Basque Country before returning home to open his own place.

It took several years, but eventually, Boragó drew the attention of the International Dining Mafia: it now ranks No. 37 on the "World's 50 Best Restaurants" list, and No. 4 among "Latin America's 50 Best Restaurants" – whatever the heck those rankings mean. I think the whole concept of these numerical rankings is goofy, before even addressing the many other valid criticisms lodged against the "50 Best" list. But it can still be a useful tool for finding restaurants, particularly in regions that don't get as much critical attention otherwise.

One of those criticisms is that the restaurants on the list tend to have a certain sameness to them: high-end, expensive tasting menus, chasing the same fashionable ingredient trends, plated according to the same aesthetic. On the surface, Boragó might seem to fall into that camp: another pricey, tasting-menu place. But from its inception, Boragó set out to explore the largely unheralded ingredients and cooking methods of Chile's native peoples, and it dives deep. When you order the "Endemíca" tasting menu at Boragó, you are given not a menu, but a map: literally, a map of Chile, stretching along the Pacific coast of South America from the northern desert of Atacama to the Tierra del Fuego in the south, the last stop before Antarctica.

My recap here reconstructs what I have gathered about our meal from the contemporaneous descriptions as they were presented (which came at us in a mix of English and sometimes rapid-fire Spanish, depending on who brought the dish to the table), Instagram posts from Chef Guzman, and some independent research after the fact.

(You can see all my pictures in this Boragó - Santiago, Chile flickr set).

A "chilenito" is usually a sweet layered cookie like an alfajor filled with manjar (milk caramel, a/k/a dulce de leche); but here, as the first bite of the meal, it took the form of a thin, crisp cracker layered with creme fraiche, tart sea strawberry, and as the top layer, a preserved edible leaf. Sea strawberry would be the first of many ingredients I'd never encountered before. Called "frutilla de mar" in Chile, it's a coastal succulent with a tangy-sweet flavor that is indeed similar to strawberry, with a hint of salt.[1]

Even with after-the-fact googling, I couldn't figure out why this dish was called "chuchum" on the menu we received after the dinner. Served balanced on some branches, it was like a miniature tart in a potato shell with layers of locos (Chilean abalone), creme fraiche and membrillo.

The next course was served in a wide ceramic bowl, which was brought to the table wrapped in cloth. Inside the bowl was a "chupe" – a stew – of wild mushrooms from Quintay, a town on the Pacific coast due west from Santiago. At the base of the bowl was a thick purée of the richly flavored mushrooms, which had been hung over embers for five hours. Arranged above the purée were several pickled and dehydrated leaves. The server finished the dish by pouring into the bowl whey from pajarito (kefir?) yogurt which had been infused with eucalyptus. This was like the flavors of a forest, concentrated in one bowl: the earthy, meaty mushrooms, their flavors deepened over the smoke; the pickled leaves; the woodsy scent of eucalyptus, all of it pulled together in the lactic tang of the whey. It was a unique and memorable dish.

(continued ...)

It took several years, but eventually, Boragó drew the attention of the International Dining Mafia: it now ranks No. 37 on the "World's 50 Best Restaurants" list, and No. 4 among "Latin America's 50 Best Restaurants" – whatever the heck those rankings mean. I think the whole concept of these numerical rankings is goofy, before even addressing the many other valid criticisms lodged against the "50 Best" list. But it can still be a useful tool for finding restaurants, particularly in regions that don't get as much critical attention otherwise.

One of those criticisms is that the restaurants on the list tend to have a certain sameness to them: high-end, expensive tasting menus, chasing the same fashionable ingredient trends, plated according to the same aesthetic. On the surface, Boragó might seem to fall into that camp: another pricey, tasting-menu place. But from its inception, Boragó set out to explore the largely unheralded ingredients and cooking methods of Chile's native peoples, and it dives deep. When you order the "Endemíca" tasting menu at Boragó, you are given not a menu, but a map: literally, a map of Chile, stretching along the Pacific coast of South America from the northern desert of Atacama to the Tierra del Fuego in the south, the last stop before Antarctica.

My recap here reconstructs what I have gathered about our meal from the contemporaneous descriptions as they were presented (which came at us in a mix of English and sometimes rapid-fire Spanish, depending on who brought the dish to the table), Instagram posts from Chef Guzman, and some independent research after the fact.

(You can see all my pictures in this Boragó - Santiago, Chile flickr set).

|

| chilenito |

|

| chuchum |

|

| chupe de hongos de Quintay |

(continued ...)

Thursday, March 3, 2016

best thing i ate last week (feb. 15-21): beef, chimichurri, lettuce cores at Alinea Miami pop-up

But the surreal has become real. While their Chicago home, which opened in 2005, gets a facelift, the Alinea team has been doing a traveling road show: first a couple weeks in Madrid, and starting a few weeks ago, a run here in Miami at the Faena Hotel.

(You can see all my pictures in this Alinea in Miami flickr set).

I was there on February 18, the day after the opening, and overall, was very impressed by how well they played for a road game. The menu included both some "greatest hits" from the Alinea oeuvre – hot potato cold potato, black truffle explosion, the bacon trapeze – as well as a few items that took inspiration from the local flavors.

From this latter category came my favorite dish of the evening, and of the week. To save a bit of the mystery of the dinner, I won't tell how the steak was cooked, other than to say that sometimes things are hidden in plain view. But I will say that the tranche of crimson-hued wagyu beef was paired with a bright tangy green emulsion inspired by Argentinian chimichurri, complemented by my favorite item on the plate: spears of crunchy, tart pickled lettuce cores, a really effective use of an unheralded and unexpected ingredient.

Although the Alinea Miami dinners have been reported as sold out for several weeks, when I checked this morning a few open spots were showing up in their ticketing system for this weekend and next. If you're intrigued, you may want to jump on those quickly.

Tuesday, September 8, 2015

Coi - San Francisco

There's a passage in Daniel Patterson's book "Coi: Stories and Recipes" that I found almost painfully evocative. The chef was writing about his first restaurant in Sonoma, and the turning of the season from summer to fall:

It was when the rains came, and the tourists went away. The first year the bills piled up on the mantelpiece at home, one pile per week, carefully bound with a rubber band, the total owed marked on a Post-it on top. At first there were two, then four and later eight piles, sitting there as a constant reminder of our empty dining room. The rain cut off roads and flooded fields, seeping into our subterranean bedroom at home, filling it with the smell of damp concrete and mold. Subsequent years were never as bad as the first, but every fall after that, as the days shortened and our bank account dwindled, my heart broke a little as we dug in for an isolated, depressing winter. That was some time ago, but the scars still remain. Every year, even now, when I step outside and feel that the light has changed, that it is fall and that summer is gone, I fight down a rising panic. It will be all right, I tell myself, over and over, until eventually I believe it enough to keep going.Coi is one of the more unusual "cookbooks" I've read lately. It's not so much the format, which pairs a thoughtful one-page essay with each recipe, nor even the initially somewhat distracting decision to put all the ingredients and quantities for those recipes in a separate index at the back of the book. And while Patterson can wax seriously eloquent about what inspires his dishes and how to cook them, it wasn't entirely that either. What was so striking was his willingness to provide these personal and often brutally candid insights into the fears and frustrations of being a professional chef.

The restaurant business is a weird and particularly tough one that seems to be constantly teetering between success and failure, both on a macro and micro level. In a sea of competition, it's hard enough to figure out what's going to capture the dining audience's interest. Then you actually have to make it work. Even when you do, this year's hot-spot can quickly turn into next year's has-been. Get all the big things right, and you're still only as good as your last plate: some line cook screws up the seasoning or cooking time on one dish, or your server is having a lousy day, and a customer leaves with a bad impression that you may never have a second chance to remedy.

From reading his book and following his career, it's clear Patterson recognizes and, in his own way, embraces this dance on the edge. In the essay about his "beet rose," an almost absurdly labor-intensive dish in which slivers of roasted beet are assembled by hand to resemble the petals of a rose, then paired with an aerated yogurt and rose petal granita, he describes it like this:

When a dish is right, there is synchronicity between form and substance, idea and execution. This is a dish that was meant to be challenging to make, impractical to reproduce. There is something about its unreasonableness which makes it more impactful. For it to work, everything has to be perfect. ... But I came to love it most for what it represented to me: intuitive, handmade cooking. Each rose is a little different, and I can pick out who made which one every night. The seasoning is finely tuned, wobbling on the edge of sweet and savory, always close to tumbling into failure.That sounds a little crazy, but yeah, I'd like to experience that. Because as good a writer as he is, Patterson is pretty universally recognized to be an even better chef. And yet I'd never paid a visit to the restaurant from which the book takes its name. My travels to the West Coast are almost always with family, which means my opportunities to do tasting menus are limited. And other, shinier objects always seemed to beckon. Then a month ago, Patterson announced that he was stepping down as executive chef at Coi and handing over the reigns to chef Matthew Kirkley in January. It was a surprising announcement: first, because Patterson's work at Coi has been so highly regarded, but even more so because it has been so definitively Patterson's restaurant, and his style of cooking is so personal, that the two seemed inseparable.[1]

We already had a trip to San Francisco coming up. So this would likely be the last chance, for the foreseeable future anyway, to catch Patterson in the kitchen. I re-jiggered the agenda, talked the family into doing a tasting menu dinner,[2] and booked a reservation at Coi. When they asked me what kind of restaurant it is, I wasn't sure exactly how to answer. What I knew is that it's a tasting menu format (but much more restrained than the 20+ course bacchanals like Saison); that it's got some locavore / forager sensibilities, but is not wedded to them; and that the cooking uses, but does not seem defined by, contemporary techniques and processes. This undefinability is also something of which Patterson is acutely self-aware:

When it comes to what a marketing wonk would call 'brand clarity,' we don't do ourselves any favors. ... When someone asks, 'What's the food like?' the best thing I can come up with is, 'Um, hopefully delicious,' my voice rising at the end in a note of uncertainty.Well, let's see.

For this farewell tour of sorts, Patterson has seeded the menu with several "greatest hits," and his "California Bowl" is one of those. It's really just an elevated version of chips and dip using some of the basic tropes of California hippie cuisine: brown rice, avocado and sprouts. But those chips (made from rice cooked down to a paste, dehydrated, then fried like chicharrones) are light and airy and have a tingle of spice, the avocado is whipped until soft as a cloud, and zinging with lime, the tiny greens have bright, fresh, intense flavors.

(You can see all my pictures from the dinner in this Coi - San Francisco flickr set).

(continued ...)

Wednesday, August 5, 2015

Alter - Miami (Wynwood)

About four years ago I came across a blog called "The Power of a Passion." It was the product of a young chef who had recently moved to Miami after working in Chicago – first a brief tour of duty at Alinea, then a year and a half at L2O during chef Laurent Gras' tenure, followed by a stint as pastry sous chef at Boka, then a move to executive sous chef at Epic. He'd come here to take a position as sous chef at Azul restaurant, where Chef Joel Huff had recently been put in place as executive chef.

The author was Bradley Kilgore. And it may have been those blog posts as much as anything that prompted our interest in doing a Cobaya dinner at Azul – one which ended up being filmed by Andrew Zimmern and featured in an episode of Bizarre Foods. Anyone who was at that dinner – which included at least one course that was Brad's creation – could sense that Kilgore had some real talent.[1]

Several months later we made a return visit to Azul; Huff was gone and the kitchen was now in the hands of Kilgore and chef de cuisine Jacob Anaya. We gave Brad free reign and he put together a sensational meal. His "anatomy of a suckling pig" remains one of the most epic pork-fests I've ever experienced.

Shortly after, Kilgore got an opportunity to run his own spot, and opened Exit 1 in Key Biscayne. But for a lot of reasons that didn't work out. The location was far from ideal, the owners were not exactly veteran operators,[2] and while Brad could cook, he may have been a bit inexperienced himself in all of the other components involved in running a restaurant. That didn't last long, but a better opportunity rolled around when he took over the chef de cuisine position at J&G Grill in Bal Harbour. Here was an established high-end restaurant in the empire of one of the most successful restaurateurs in the world (Jean-Georges Vongerichten), with the bonus of getting to team up with one of Miami's brightest stars: pastry chef Antonio Bachour. Sure, Brad was mostly executing Jean-Georges' best hits, but he also got a little bit of leash to do his own thing too, including some really exceptional on-request tasting menus.

So I was a bit surprised when last November, after a little more than a year at J&G, Kilgore announced that he was leaving to open his own restaurant. As talented as I knew him to be, I'll confess I was concerned that it was too soon. The last thing I wanted – for him, and frankly, for myself as someone who really enjoyed eating his food – was another exit like Exit 1.

I was wrong. He was ready. And his new restaurant – Alter, in Wynwood, which opened in late May – is already one of the best restaurants in Miami.[3]

(You can see all my pictures in this Alter - Miami (Wynwood) flickr set; pictured at top, a pre-dessert of assorted local tropical fruits in a crisp candy shell, served on an inverted woven palm frond basket).

The space, in the burgeoning Wynwood arts district,[4] has a minimalist, industrial feel: the cinder block walls are bare, the ductwork is exposed, the primary decoration is an abstract squiggle of hot pink neon hanging over the liquor shelf that separates the open kitchen from the dining room. The dark-stained wood tables seat about forty, with a small extra seating area outside if the temperatures ever drop. The room can get too warm when it's crowded and too loud when the music's cranked up, both of which are frequent occurrences.

The menu is nearly as spare as the decor. There are usually about eight appetizers and a comparable number of main courses; a five-course tasting menu ($65) is composed from the kitchen's choice of several of those items, some in shrunken-down portions, and is both a solid value and a particularly smart option for a first visit.

Lots of places have fish tartare on their menus these days. Nobody has one like this. Multi-hued batons of green mango and various radishes form a haystack on top of precisely diced fish, the exact species of which is dictated by whatever is local and fresh. There are celery leaves,[5] there's dried soy, there's yuzu kosho, there's black lime zested over the top. It's simultaneously spicy, citrusy, smoky, green, and fresh, as the flavors ping-pong between suggestions of a Thai pok-pok salad and a Peruvian ceviche and other things entirely.

A "signature dish" can be both blessing and curse. It helps define a style – and bring customers in – but can also be a sort of trap, something that can never come off the menu. Alter's soft egg may be its signature dish, and I'm sure it's much too early for Brad to be worried about golden handcuffs.[6] A fluffy, brûléed scallop mousse, bearing just a subtle whiff of the ocean (turn up the volume with an optional dollop of Florida caviar), blankets a runny-yolked, soft-cooked egg hidden within. Also suspended underneath the surface are truffle pearls and a crackly shard of gruyere cheese, like those crusty bits on the side of the bowl that are maybe the best thing about French onion soup.

As signatures go, this is a fitting one for the cooking at Alter. The dish – like much of Brad's work – is a deftly executed balancing act between delicate subtlety and outright indulgence, earth and ocean, creamy and rich without being heavy and cloying. It also displays another thing I see often in Brad's cooking: the incorporation of dessert techniques into savory dishes, what with the mousse and the brûlée, inverting the past decade's trend of incorporating savory elements into desserts. Pro tip: if you're getting the egg, you really also need to get the "bread & beurre," a tender-crumbed miniature loaf crusted with sumac and dill seed, and served with whipped, shoyu-bolstered "umami butter." The bread is delicious on its own, but as a tool for getting every last bit of the egg, it is particularly effective.

Summer squash is often among the most nebbish of vegetables. Not here. Zucchini and yellow squashes are cooked just enough to temper their bitter, raw edge, but not so much as to turn watery and slimy. A green circle of an herbaceous, dill-infused purée serves as the base for their arrangement, which is interspersed with dabs of tart, creamy lemon curd.[7] Crumbles of soft feta cheese, a touch of citron vinaigrette, a tangle of crisp, fresh greens and some crunchy puffed wild rice complete the dish. It works a magical transformation on the squash, like a sexy librarian taking off her glasses and letting down her hair.

(continued ...)

Friday, March 20, 2015

Cobaya Five 0 with Chefs Jeremiah Bullfrog and H. Alexander Talbot

I will save most of the nostalgic reminiscences for another post, but this was a special one: our 50th Cobaya dinner. When we started this little experiment nearly six years ago, I had no idea if we'd get enough people to show up for a single dinner, much less be able to do it 49 more times. So it was particularly appropriate that we got to do Cobaya Five 0 with some people who have been a big part of our story.

Chef Jeremiah Bullfrog was one of the first people to reach out to us when we started on this endeavor – this was before gastroPod v.1.0, much less v.2.0 in a shipping container in Wynwood (and the new v.2.5 in Aventura Mall). He cooked for Experiment #2, made a return a couple years later for Experiment #19, and has helped out on countless other events.

H. Alexander Talbot – one of the co-creators, along with wife Aki Kamozawa, of the Ideas in Food blog, and co-author of "Ideas In Food: Great Recipes and Why They Work" and "Maximum Flavor: Recipes That Will Change the Way You Cook" – has been an inspiration and mentor to many of the chefs with whom we've worked. He was also back for a reunion with us after doing Experiment #10 almost exactly four years ago.

And Kurtis Jantz, Executive Chef at the Trump International Beach Resort in Sunny Isles, was really the original inspiration for these dinners. Before there was Cobaya, there were the "Paradigm" dinners that Kurtis and then-sous chef Chad Galiano were doing. It was while waiting in the valet circle at the Trump that the idea for this Cobaya thing was hatched. The Cobaya Gras dinner Kurtis and Chad put on remains one of my favorite of any of our events. So it was great to have him churning out the snacks for #50.

Another guy who was at Chef Jeremiah's Experiment #2: Steve Santana. Back then, he was a coder who had convinced his firm to play host to one of our dinners in a penthouse office in Midtown. Now he's the chef at Taquiza, a great taqueria in South Beach, and has also had a backstage hand in many of our events. I was really touched to hear in an interview on ChatChow.com that he credits that Cobaya dinner with steering him toward a career in the kitchen.

But I said I would save the trip down memory lane for another post, so let's talk about this dinner, because it was a great one.

(You can see all my pictures in this Cobaya Five 0 flickr set).

(continued ...)

Chef Jeremiah Bullfrog was one of the first people to reach out to us when we started on this endeavor – this was before gastroPod v.1.0, much less v.2.0 in a shipping container in Wynwood (and the new v.2.5 in Aventura Mall). He cooked for Experiment #2, made a return a couple years later for Experiment #19, and has helped out on countless other events.

H. Alexander Talbot – one of the co-creators, along with wife Aki Kamozawa, of the Ideas in Food blog, and co-author of "Ideas In Food: Great Recipes and Why They Work" and "Maximum Flavor: Recipes That Will Change the Way You Cook" – has been an inspiration and mentor to many of the chefs with whom we've worked. He was also back for a reunion with us after doing Experiment #10 almost exactly four years ago.

And Kurtis Jantz, Executive Chef at the Trump International Beach Resort in Sunny Isles, was really the original inspiration for these dinners. Before there was Cobaya, there were the "Paradigm" dinners that Kurtis and then-sous chef Chad Galiano were doing. It was while waiting in the valet circle at the Trump that the idea for this Cobaya thing was hatched. The Cobaya Gras dinner Kurtis and Chad put on remains one of my favorite of any of our events. So it was great to have him churning out the snacks for #50.

Another guy who was at Chef Jeremiah's Experiment #2: Steve Santana. Back then, he was a coder who had convinced his firm to play host to one of our dinners in a penthouse office in Midtown. Now he's the chef at Taquiza, a great taqueria in South Beach, and has also had a backstage hand in many of our events. I was really touched to hear in an interview on ChatChow.com that he credits that Cobaya dinner with steering him toward a career in the kitchen.

But I said I would save the trip down memory lane for another post, so let's talk about this dinner, because it was a great one.

(You can see all my pictures in this Cobaya Five 0 flickr set).

(continued ...)

Monday, November 17, 2014

Alinea - Chicago

The idea of dinner as spectacle is hardly a new one. In the Satyricon, Petronius recounts the (fictional) dinner of Trimalchio, featuring such delicacies as pea hen eggs filled with tiny songbirds, a hare with wings affixed to it to look like a pegasus, and a whole wild boar with baskets of dates hanging from its tusks, surrounded by pastry piglets and stuffed with live thrushes – preceded by a presentation of hunting-themed tapestries and a pack of hunting dogs traipsing through the dining room to set the mood.

Fast forward a couple thousand years, and recently Jeremiah Tower – one of the titans of the 1980's dining universe, who is returning to the business on a mission to resuscitate the Tavern on the Green – spoke with Andrew Friedman about the theater of dining at TOTG:

My first meal at Alinea was a long time ago, within a couple years of its opening. They were the heady days of foams and spheres and fluid gels – back when what is now inaptly named "modernist cuisine" went by the equally inapt "molecular gastronomy." On that first visit, we had bacon swinging on trapezes, bites perched on bobbing "antennae," and dishes nestled on pillows emitting flower-perfumed air. But perhaps the most striking oddity of it all was the somber, ramrod-stiff waitstaff. There was a huge disconnect between the playfulness coming out of Grant Achatz's kitchen and the solemnity of those who served it, as if the food wouldn't be taken seriously enough if they actually cracked a smile.

Achatz no longer needs to be concerned with being taken seriously: Alinea now has three Michelin stars, a No. 9 position on San Pellegrino's 50 Best Restaurants list, and multiple James Beard awards to vouch for that. And everyone's smiling.[1]

(You can see all my pictures in this Alinea - October 2014 flickr set.)

I'd not been back to Alinea until last month,[2] when the opportunity for a return visit fortuitously arose. The gap afforded an interesting time-lapse view of the restaurant's maturation. Many things that were still just in the concept stage at the time of my initial visit – reincorporating classical old-school dishes and table-side service, the now-famous dessert on the table – are now firmly entrenched in the repertoire.[3] Dishes that were once emblematic of Alinea's cutting edge creativity – like the "hot potato cold potato" pictured above – are now signature dishes, evoking more nostalgia than awe (for a repeat visitor anyway).

There is also plenty that's new, and plenty that's still awe-inspiring. But what was most notable to me, given my peculiar perspective, is how the front of the house at Alinea has caught up with the back. This is now a fully realized experience where the food and the spectacle of its presentation are on equal footing. As to whether or not that's a good thing – I'll try to address after the recap of my recent visit.

It's hard to imagine a more traditional way to commence a meal than with caviar and champagne. It's hard to come up with a better one either. The accompaniments to the caviar here are customary ones, but of course transformed: a brioche foam, an egg yolk emulsion, a transparent gelée flavored with onion and capers. The osetra caviar itself was excellent, as was the Pierre Moncuit champagne.

Then the show really starts. Servers arrive wielding blocks of ice that are 1/25 size replicas of the iceberg that sunk the Titanic,[4] strewn with a sort of reinvented seafood platter: a sphere of oyster liquor and mignonette sauce nestled in the oyster's shell; strips of chewy clam glazed with unagi sauce, served ishiyaki style on a hot rock; a sort of deconstructed miso soup with kombu and crumbles of miso and bonito; a sort of reconstructed tomato of fresh tuna; a shooter of Asian pear and yuzu juices dug right into the block of ice, with a fat glass straw planted in it (which, awkwardly, was too long to use without actually standing up at the table); and a cylindrical sea urchin cake, infused with vanilla, wrapped in nori, and topped with lemon zest and coarse salt, poised right between savory and sweet.

(continued ...)

Fast forward a couple thousand years, and recently Jeremiah Tower – one of the titans of the 1980's dining universe, who is returning to the business on a mission to resuscitate the Tavern on the Green – spoke with Andrew Friedman about the theater of dining at TOTG:

Friedman: When you say outrageous, what do you mean, for people who weren't there back in the day?So in a sense, what Alinea is doing is nothing new. But few contemporary restaurants I've visited have the same dedication to the theater of dinner.

Tower: Oh, I mean, my God. Oversized chandeliers and didn't he put live animals at one point for some party? It reminded me of the Ritz, a nouveau riche version of the Ritz, where in the old days, a grand Duke wanted a winter scene so they flooded the basement and froze it and draped everything in ice. It was that kind of theater.

Friedman: What do you remember about the food at the old Tavern?

Tower: You know, I honestly don’t remember anything. I've been looking at old menus from the 1950s but I don’t think I ever looked at the plate. I was too busy looking at the decor and the action.

My first meal at Alinea was a long time ago, within a couple years of its opening. They were the heady days of foams and spheres and fluid gels – back when what is now inaptly named "modernist cuisine" went by the equally inapt "molecular gastronomy." On that first visit, we had bacon swinging on trapezes, bites perched on bobbing "antennae," and dishes nestled on pillows emitting flower-perfumed air. But perhaps the most striking oddity of it all was the somber, ramrod-stiff waitstaff. There was a huge disconnect between the playfulness coming out of Grant Achatz's kitchen and the solemnity of those who served it, as if the food wouldn't be taken seriously enough if they actually cracked a smile.

Achatz no longer needs to be concerned with being taken seriously: Alinea now has three Michelin stars, a No. 9 position on San Pellegrino's 50 Best Restaurants list, and multiple James Beard awards to vouch for that. And everyone's smiling.[1]

(You can see all my pictures in this Alinea - October 2014 flickr set.)

I'd not been back to Alinea until last month,[2] when the opportunity for a return visit fortuitously arose. The gap afforded an interesting time-lapse view of the restaurant's maturation. Many things that were still just in the concept stage at the time of my initial visit – reincorporating classical old-school dishes and table-side service, the now-famous dessert on the table – are now firmly entrenched in the repertoire.[3] Dishes that were once emblematic of Alinea's cutting edge creativity – like the "hot potato cold potato" pictured above – are now signature dishes, evoking more nostalgia than awe (for a repeat visitor anyway).

There is also plenty that's new, and plenty that's still awe-inspiring. But what was most notable to me, given my peculiar perspective, is how the front of the house at Alinea has caught up with the back. This is now a fully realized experience where the food and the spectacle of its presentation are on equal footing. As to whether or not that's a good thing – I'll try to address after the recap of my recent visit.

It's hard to imagine a more traditional way to commence a meal than with caviar and champagne. It's hard to come up with a better one either. The accompaniments to the caviar here are customary ones, but of course transformed: a brioche foam, an egg yolk emulsion, a transparent gelée flavored with onion and capers. The osetra caviar itself was excellent, as was the Pierre Moncuit champagne.

Then the show really starts. Servers arrive wielding blocks of ice that are 1/25 size replicas of the iceberg that sunk the Titanic,[4] strewn with a sort of reinvented seafood platter: a sphere of oyster liquor and mignonette sauce nestled in the oyster's shell; strips of chewy clam glazed with unagi sauce, served ishiyaki style on a hot rock; a sort of deconstructed miso soup with kombu and crumbles of miso and bonito; a sort of reconstructed tomato of fresh tuna; a shooter of Asian pear and yuzu juices dug right into the block of ice, with a fat glass straw planted in it (which, awkwardly, was too long to use without actually standing up at the table); and a cylindrical sea urchin cake, infused with vanilla, wrapped in nori, and topped with lemon zest and coarse salt, poised right between savory and sweet.

(continued ...)

Monday, November 10, 2014

L2O - Chicago

I was looking forward to writing about my meal at L2O in Chicago last month. I didn't realize it was going to be a eulogy.

L2O first vaulted to prominence in 2008, when the Lettuce Entertain You Enterprises group lured chef Laurent Gras from San Francisco to open a high-end, seafood-focused restaurant in Chicago. In 2010, L2O earned three Michelin stars; that same month, Gras left. The next year, Matthew Kirkley took over as chef de cuisine and eventually was elevated to executive chef. Many quietly said that the restaurant under Kirkley was every bit as good – if not better – than under Gras' reign.

Now comes news that the restaurant will be closing at the end of the year. On one hand, it's a big surprise: L2O is one of the city's – and country's – most highly regarded restaurants, even if it doesn't seem to draw the same quantum of attention as the venues of Chicago royalty like Grant Achatz, Rick Bayless, and Paul Kahan. On the other hand, L2O always seemed an odd fit with LEYE, which is better known (to me, anyway) for crowd-pleaser type places like Cafe Ba-Ba-Reeba and Shaw's Crab House. LEYE's founder, Rich Melman, seemed to confirm as much:

"(L2O) had never been a money maker for us," Melman says. "As with all restaurants, it's all about volume. I don't want to do four-star restaurants anymore, at least for the foreseeable future. Three partners came out of L2O and it was successful in that way."Surprise or not, L2O's imminent closing is a disappointment: this was one of the most pleasing, satisfying meals I've had all year. It's a shame it will be my only chance to experience it.

(You can see all my pictures in this L2O flickr set.)

The tasting menu[1] starts with a series of snacks. The first is a sort of ode to Chesapeake Bay (Chef Kirkley is a Baltimore native): a few precariously balanced wafers with the puffy texture of Chinese shrimp chips, but the intense, pronounced flavors of crab and Old Bay seasoning. Next, a mussel "tart," the mollusks' flavor infused into a quivering mousse brightened with parsley and citrus, nestled in a crispy shell. Then, a puffy pomme souflée, ingeniously filled with a creamy salt cod brandade, and dusted with coffee and bergamot for a pleasingly bitter counterpoint.

Maybe it was brought into sharper focus by comparison to the theatrical pyrotechnics of Alinea, where I'd eaten the night before, but there's an austerity and minimalism to Kirkley's style that I really appreciated. Most courses featured only a few primary ingredients, the flavors of which were honed, concentrated, and often reiterated within the dish. Indeed, the composition of many plates was similar: a fish or seafood item as the primary focus, sometimes a bit of animal fat to provide richness and extend flavors, often a sauce extracted from the primary ingredients, an accent note of herb or citrus.

That pattern was set in this first course, a pink ball of langoustine[2] tartare, enriched with lardo and brightened with pickled lemon and English pea. This was followed by a Kusshi oyster, nestled in its shell under a bed of green apple and vermouth creams, and presented like some nautical bric-a-brac from Shell City. Pinkish orange ocean trout was lightly cured, presented in silky, supple ribbons complemented by the delicate but intense flavors of Chartreuse, citrus confit and airy little gougere-like poufs dusted with fines herbes.

(continued ...)

Thursday, October 23, 2014

Elements: Scott Anderson Dinner at The Dutch

Much as I might wish for it, I don't get to spend my days traversing the country from restaurant to restaurant. We're fortunate to travel often and usually eat very well when we do, but even so, there are places I'm unlikely to ever visit. Princeton, New Jersey would fall into that category.[1] And as a result, I figured I would never eat at Elements, Chef Scott Anderson's restaurant which opened in Princeton about five years ago (and is currently closed while moving to a new location).

This was cause for regret, because I'd read and heard many very good things about it. A couple guys whose opinions I value raved about their meals there. Despite being somewhat off the grid, it was highly regarded enough to make Opinionated About Dining's list of the top twenty restaurants in the U.S. So I was pretty excited when I learned, through Chef Jeremiah Bullfrog, that Scott was interested in doing a dinner here in Miami.

We sent up some Cobaya flares for other folks who might be interested, and Chef Conor Hanlon of The Dutch graciously agreed to participate and play host. Together, Scott, Jeremiah, Conor and Josh Gripper, The Dutch's pastry chef, put together a pretty extraordinary ten-course dinner.

(You can see all my pictures in this Chef Scott Anderson (Elements) at the Dutch flickr set. Apologies for the weird sepia-toned hue to these pictures; the food-unfriendly yellow lights on The Dutch's terrace are the only downside of putting on events there).

A few canapes to start: a pink beet macaron with an herbed chevre filling, a nice repurposing of a traditional combination; a crispy chicharron topped with a Thai-inspired green papaya and apple salad; and an airy – kind of fishy – scallop chip topped with pungent kimchee and trout roe. I'm assuming each chef did one of these, but they didn't tell us who (I'll guess Conor for the macaron, Jeremiah for the papaya salad, and Scott for the scallop chip).

Sometimes simple is bold. Particularly in this kind of dinner format, where the natural tendency is to show off, restraint isn't easily exercised. But that's what Jeremiah displayed, letting the main ingredient – some really lush, buttery baja yellowtail (a/k/a hiramasa or goldstriped amberjack) – stand out in his first dish. Meaty cubes and a couple silky ribbons of the raw fish were paired with a verdant fava bean purée, a few green leaves (tart sorrel, grassy tatsoi?), some slivers of shallot and a thin round of peppery black radish for some bite.

Conor followed with something also aquatic and equally elegant: cured ora king salmon, a richly fatty but clean-flavored salmon sustainably farmed off the coast of New Zealand, served with slivered radishes, puddles of deep, funky black garlic hollandaise, and hillocks of nutty crispy quinoa. The composition brought to mind a more sophisticated iteration of the combination of lox and a pumpernickel bagel that is so deeply resonant among my people.

I'm not sure how much communication there was between the chefs about their dishes, but it was interesting that Scott's first course also seemed to be a continuation of the same theme. A plump, sweet scallop (brought in live) was just barely cooked through, topped with a relish of Brazilian starfish pepper and shallots that tasted both spicy and fruity (reminiscent of habanero but with less capsicum heat), plus buttery avocado oil, a couple nasturtium leaves and a bright marigold blossom. These were assertive flavors to match with the somewhat delicate seafood, but I loved how they came together.

(continued ...)

This was cause for regret, because I'd read and heard many very good things about it. A couple guys whose opinions I value raved about their meals there. Despite being somewhat off the grid, it was highly regarded enough to make Opinionated About Dining's list of the top twenty restaurants in the U.S. So I was pretty excited when I learned, through Chef Jeremiah Bullfrog, that Scott was interested in doing a dinner here in Miami.

We sent up some Cobaya flares for other folks who might be interested, and Chef Conor Hanlon of The Dutch graciously agreed to participate and play host. Together, Scott, Jeremiah, Conor and Josh Gripper, The Dutch's pastry chef, put together a pretty extraordinary ten-course dinner.

(You can see all my pictures in this Chef Scott Anderson (Elements) at the Dutch flickr set. Apologies for the weird sepia-toned hue to these pictures; the food-unfriendly yellow lights on The Dutch's terrace are the only downside of putting on events there).

A few canapes to start: a pink beet macaron with an herbed chevre filling, a nice repurposing of a traditional combination; a crispy chicharron topped with a Thai-inspired green papaya and apple salad; and an airy – kind of fishy – scallop chip topped with pungent kimchee and trout roe. I'm assuming each chef did one of these, but they didn't tell us who (I'll guess Conor for the macaron, Jeremiah for the papaya salad, and Scott for the scallop chip).

Sometimes simple is bold. Particularly in this kind of dinner format, where the natural tendency is to show off, restraint isn't easily exercised. But that's what Jeremiah displayed, letting the main ingredient – some really lush, buttery baja yellowtail (a/k/a hiramasa or goldstriped amberjack) – stand out in his first dish. Meaty cubes and a couple silky ribbons of the raw fish were paired with a verdant fava bean purée, a few green leaves (tart sorrel, grassy tatsoi?), some slivers of shallot and a thin round of peppery black radish for some bite.

Conor followed with something also aquatic and equally elegant: cured ora king salmon, a richly fatty but clean-flavored salmon sustainably farmed off the coast of New Zealand, served with slivered radishes, puddles of deep, funky black garlic hollandaise, and hillocks of nutty crispy quinoa. The composition brought to mind a more sophisticated iteration of the combination of lox and a pumpernickel bagel that is so deeply resonant among my people.

I'm not sure how much communication there was between the chefs about their dishes, but it was interesting that Scott's first course also seemed to be a continuation of the same theme. A plump, sweet scallop (brought in live) was just barely cooked through, topped with a relish of Brazilian starfish pepper and shallots that tasted both spicy and fruity (reminiscent of habanero but with less capsicum heat), plus buttery avocado oil, a couple nasturtium leaves and a bright marigold blossom. These were assertive flavors to match with the somewhat delicate seafood, but I loved how they came together.

(continued ...)

Monday, July 28, 2014

Cobayapalooza at Shikany

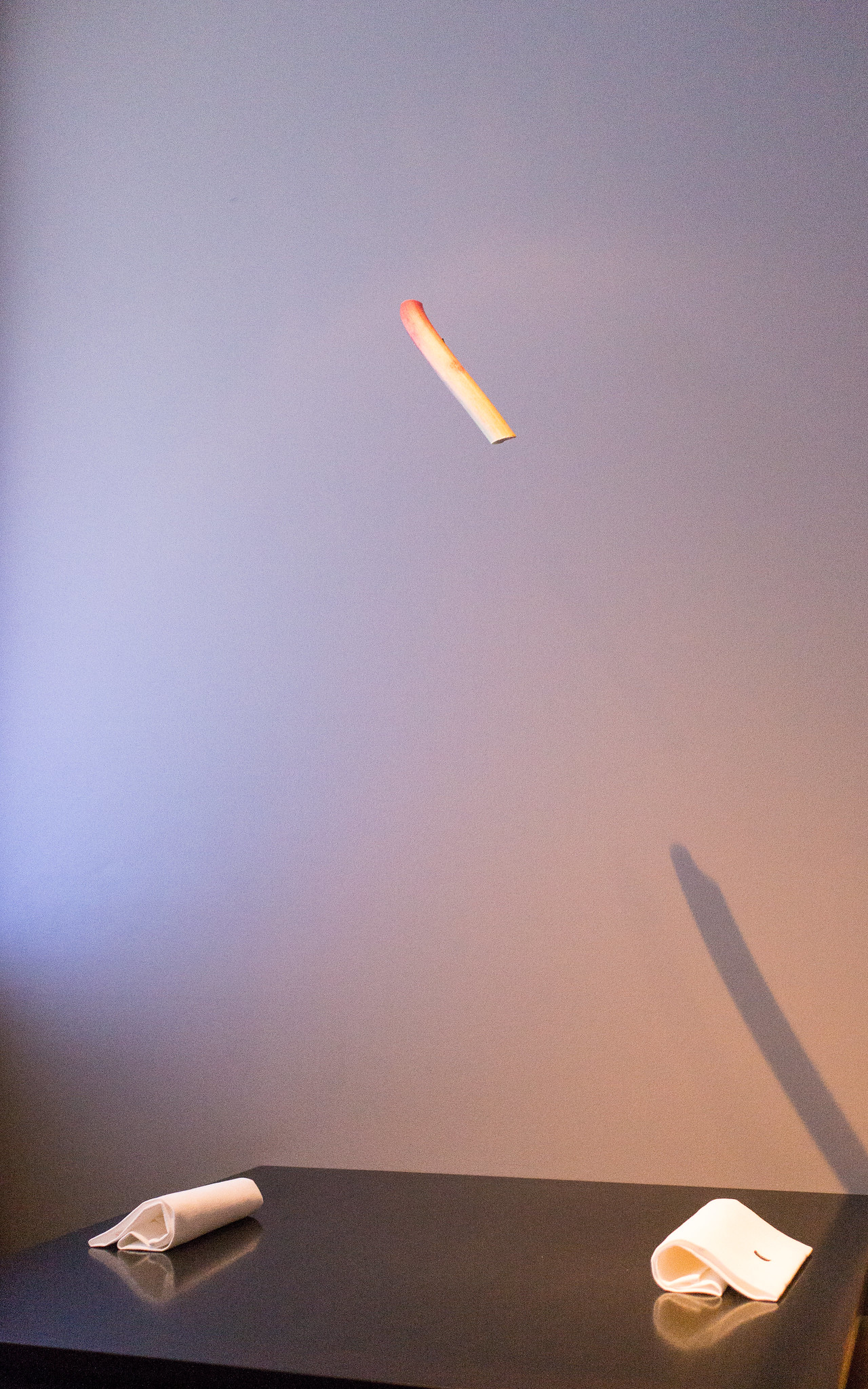

Typically, we use our Cobaya dinners as a way of turning a spotlight on a particular chef, to give them free reign to craft a menu that gives voice to their creative impulses or personal culinary obsessions. But collaboration has its rewards too, and we've long hoped to do a dinner that would bring together several local chefs to cook a meal.

That opportunity finally presented itself through the generosity of chef Michael Shikany, who opened the kitchen of his new restaurant in Wynwood – Shikany – to several other chefs for a "Cobayapalooza" dinner on July 16. Shikany and his pastry chef Jill Montinola were joined by Diego Oka of La Mar Miami, David Sears of SushiSamba Coral Gables, Mathias Gervias of the Setai, Danny Grant of 1826 Restaurant and Lounge, and Timon Balloo of Sugarcane Raw Bar Grill and Bocce Bar, who collectively put together a nine-course menu loosely organized around the great La Boîte spice blends made by Lior Lev Sercarz (each dish used a different La Boîte custom blend).

The restaurant was an ideal setting for the event, with room for nearly fifty guinea pigs in the stylish dining room, as well as for all the chefs and their crews in a bright, wide open kitchen. It was a great opportunity to highlight both an ambitious new restaurant, and a number of other talented young chefs working in Miami – several of them fairly new faces.

(You can see all my pictures in this Cobayapalooza flickr set).

Course 1 (Galil N. 13) Fresh Diver Scallop Crudo

Michael Shikany

Shikany started things off with a diver scallop crudo, thin ribbons of the shellfish topped with diced strawberries, pickled watermelon rind, and white truffle oil, and plated with a swoop of black garlic aioli, a powdered creme fraiche sorbet, dots of hibiscus gel and still more items I've lost track of. A lot of flavors, a lot of techniques; but also a really good, fresh, plump, sweet scallop as the centerpiece of it all.

Course 2 (Coquelicot N. 24) Oysters & Salmon

David Sears

Next up, David Sears of SushiSamba, who served a round of tender salmon topped with a crust of poppy seeds and spices (almost an "everything bagel" kind of thing going on here), accompanied by a tangled salad of sorts of oysters, pickled onions and sweet cherry tomatoes, accompanied by generous dollops of jet black sturgeon caviar and cool creme fraiche.

Course 3 (Luberon N. 4) Wild Quahog

Michael Shikany

Back to Shikany for the next course, a sort of cross between sashimi and ceviche featuring – among other things – a fat quahog clam, ribbons of madai (Japanese sea bream), assorted seaweeds, cubes of tofu and purple Okinawa potato, dabs of puréed sweet potato, tiny caviar of "Coke syrup," an herbaceous green emulsion, and a little squirt bottle of a spicy soy sauce to apply in DIY fashion. I think the perfumey, lavender-forward Luberon spice blend was making its appearance in the dabs of translucent fluid gel interspersed around the fish.

Course 4 (Vadouvan N. 28) Yellowtail Snapper

Diego Oka

Diego Oka's yellowtail dish was, for me, one of the most intriguing of the night. While ceviche tends to get all the attention these days, there's an incredible diversity to Peruvian cooking, which his dish highlighted. The fish was served over a curry-spiced, chocolate-dusted potato stew, which had a fascinating, nubby texture and great depth of flavor.A translucent quinoa crisp, peanut butter powder and a sauce of huacatay (Peruvian black mint, with a zing sort of between typical mint and basil) completed the dish.

(continued ...)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)