Japan would seem to have a massive trade surplus when it comes to culinary inspiration. From the minimalist lightness of French nouvelle cuisine of the 1970's, to America's never-ending if not always quality-driven fixation on sushi, to "fusion" in so many guises, to this past decade's ramen craze, the traffic in ideas appears to be largely outbound. But Japan also absorbs influences too; and when it does so, it's usually with the same intense dedication to craft that pervades virtually all other pursuits there.[1]

Azabu Kadowaki is a resolutely Japanese restaurant; in fact, chef Toshiya Kadowaki was famed for turning down stars when the Michelin guide first came to Japan, on the basis that “Japanese food was created here, and only Japanese know it ... How can a bunch of foreigners show up and tell us what is good or bad?” (He ultimately relented, as the restaurant now has two of those stars that Kadowaki initially shunned.) But it also clearly bears the mark of some Western influences, filtered through a Japanese prism.

If I have my genres right, Kadowaki is a "kappo ryori" restaurant – high end food served straight from the kitchen, usually by the chef himself presenting it across the counter. It is an elegantly appointed space: honed wood counters and cabinets with the precision workmanship of a luxury yacht, cooking instruments all encased in patterned ceramic. There were maybe eight seats at the bar that faced that gorgeous open kitchen, though there appeared to be a couple private rooms as well that servers flitted in and out of.

(You can see all my pictures in this Azabu Kadowaki flickr set.)

The meal is omakase style: other than a diner's selection between snow crab and fugu as a "main" course, and between three different price points (all designated when the reservation is booked), everything else is chef's choice.

Our dinner started with an unusual and beautiful dish: a block of rich, nutty sesame tofu, nestled in a bed of magenta-hued beet miso, crowned with some meaty roasted mushrooms and bright purple flower buds. It defied any stereotype of a tofu-based dish being bland or insubstantial.

Almost simultaneously, we were also served a block of what I believe was either mochi or konnyaku (a/k/a yam cake or devil's tongue jelly). Toasted around the edges, it was chewy, almost elastic in texture, and blandly starchy in flavor other than the dab of freshly grated wasabi. It was texturally intriguing, but I can't say much more about it than that.

The next course was one of my favorites, blending eastern and western components: a cube of winter daikon radish draped with a slice of roasted pear, all enrobed in a creamy cod roe sauce and topped with a fine julienne of fresh black truffle. Cooked daikon is a highly underrated ingredient: tender but still having substance, silky but with a pleasing bite of graininess against the teeth, and a mild sweet flavor. Those qualities were mirrored and amplified by the roasted pear, which brought a more intense caramelized sweetness, the mildly salty, creamy sauce, and the earthy, aromatic truffle. There were no bold flavors here – rather it was all subtlety and grace.

(continued ...)

Wednesday, May 21, 2014

Monday, May 19, 2014

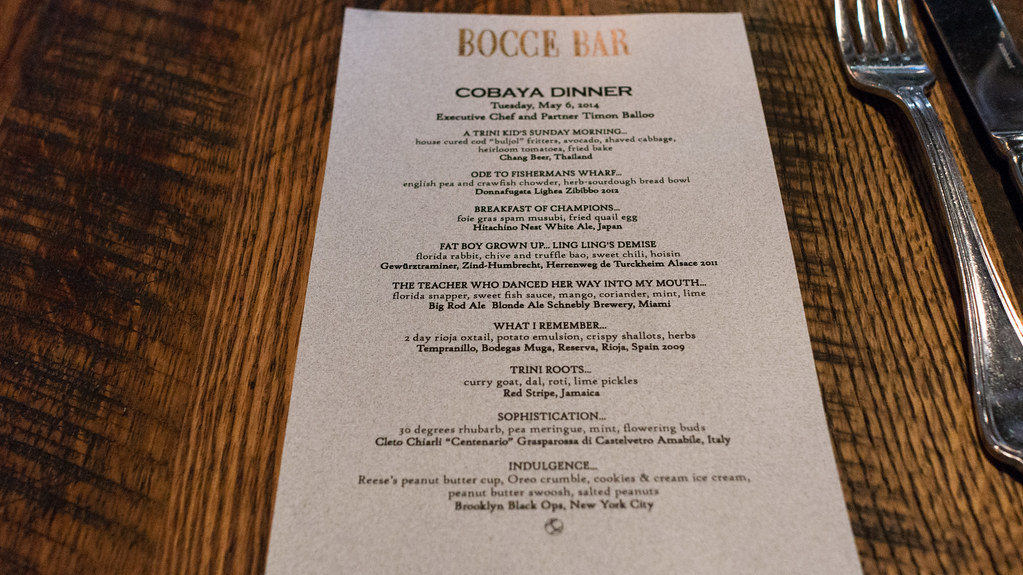

CobayaBalloo - Chef Timon Balloo at Bocce Bar

I love a meal that tells a good story. A meal can be a journey – like Norman Van Aken's menus, traversing the flavors of the Caribbean, Asia, Latin America and Iberia. Some of the best are those that aspire to simply reflect a time and place – the flavor of the here and now, as Blaine Wetzel does to such great success at Willows Inn. Still others are more personal, attempting to recapture a particular taste memory or flavor sensation – that tunnel-vision view into a childhood experience so magnificently captured in the film Ratatouille.

This last type is often the most difficult to pull off, because there is no guarantee everyone has the same memory bank of experiences, or that they were absorbed in the same way. (For more thoughts on "story food" and capturing food memories, read this recent piece by Bruce Palling in "Cutting Edge Chefs Serve Up Food That Tells a Story"). Getting the backstory is helpful, which is part of why interaction can be a key to a meaningful dining experience.

Chef Timon Balloo took the autobiographical approach to the Cobaya dinner he put on last week, putting together a menu that told the story of his life in food. He also did a great job filling in the backstory which wound a meandering path from a Trinidadian childhood breakfast to the two Midtown Miami restaurants – Sugarcane Raw Bar Grill and Bocce Bar – that he runs today.

(You can see all my pictures in this CobayaBalloo flickr set).

Our group of nearly forty guinea pigs took over several large tables set in front of the open kitchen of Bocce Bar, which recently opened a few doors down from Sugarcane in the space which was formerly occupied by Sustain. As we always do, we told Timon that we didn't want "Sugarcane" food or "Bocce Bar" food – we wanted "Timon" food. He did exactly that, with a nine-course menu that paid tribute to his culinary influences and inspirations.

Growing up in a Trinidadian family, this was a typical weekend breakfast – salt cod tossed with shredded cabbage, tomatoes and fresh herbs, tucked into "bake," a simple, dense, chewy bread (you may have also heard of "Bake and Shark," another typical Trini recipe). This doesn't look or sound like much, but it was one of the dishes of the night for me, and a great start to our meal.[1] The snappy, spicy Chang Beer pairing was also right on target, as were all the pairings, which smartly and effectively featured beers as often as wines.

Chef Balloo spent some formative years in San Francisco, and while there are several potential candidates for an iconic San Francisco dish, the chowder in a sourdough bread bowl served at dozens of spots along Fisherman's Wharf may be the most ubiquitous. Timon stuck with the classic format but put a seasonal spin on the ingredients, subbing in a crawfish bisque studded with English peas for the typical clam and potato chowder.

(continued ...)

This last type is often the most difficult to pull off, because there is no guarantee everyone has the same memory bank of experiences, or that they were absorbed in the same way. (For more thoughts on "story food" and capturing food memories, read this recent piece by Bruce Palling in "Cutting Edge Chefs Serve Up Food That Tells a Story"). Getting the backstory is helpful, which is part of why interaction can be a key to a meaningful dining experience.

Chef Timon Balloo took the autobiographical approach to the Cobaya dinner he put on last week, putting together a menu that told the story of his life in food. He also did a great job filling in the backstory which wound a meandering path from a Trinidadian childhood breakfast to the two Midtown Miami restaurants – Sugarcane Raw Bar Grill and Bocce Bar – that he runs today.

(You can see all my pictures in this CobayaBalloo flickr set).

Our group of nearly forty guinea pigs took over several large tables set in front of the open kitchen of Bocce Bar, which recently opened a few doors down from Sugarcane in the space which was formerly occupied by Sustain. As we always do, we told Timon that we didn't want "Sugarcane" food or "Bocce Bar" food – we wanted "Timon" food. He did exactly that, with a nine-course menu that paid tribute to his culinary influences and inspirations.

"A Trini Kid's Sunday Morning"

house cured cod "buljol" fritters, avocado, shaved cabbage, heirloom tomatoes, fried bake

Chang Beer, Thailand

Growing up in a Trinidadian family, this was a typical weekend breakfast – salt cod tossed with shredded cabbage, tomatoes and fresh herbs, tucked into "bake," a simple, dense, chewy bread (you may have also heard of "Bake and Shark," another typical Trini recipe). This doesn't look or sound like much, but it was one of the dishes of the night for me, and a great start to our meal.[1] The snappy, spicy Chang Beer pairing was also right on target, as were all the pairings, which smartly and effectively featured beers as often as wines.

"Ode to Fisherman's Wharf"

english pea and crawfish chowder, herb-sourdough bread bowl

Donnafugata Lighea Zibibbo 2012

Chef Balloo spent some formative years in San Francisco, and while there are several potential candidates for an iconic San Francisco dish, the chowder in a sourdough bread bowl served at dozens of spots along Fisherman's Wharf may be the most ubiquitous. Timon stuck with the classic format but put a seasonal spin on the ingredients, subbing in a crawfish bisque studded with English peas for the typical clam and potato chowder.

(continued ...)

Sunday, May 4, 2014

BlackBrick (a/k/a Midtown Chinese) - Midtown Miami

"I'm an unpure purist, something like that." - Keith Richards"Authentic" is a word I try to avoid. I'm just not convinced it means an awful lot. Too often, it's thrown about by one-upping blowhards trying to bolster their own credibility ("I spent a weekend in Cabo so I know all about 'authentic' Mexican tacos."). Even for those with more serious intentions, the definition of "authenticity" is elusive, for reasons I've kicked around before. The executive summary: "So many cuisines, even in their 'native' forms, are capable of so many infinite variations, and so many 'traditional' dishes are actually themselves the result of historical cross-cultural mash-ups that would today go by the sobriquet of 'fusion' dishes, that labeling any one particular iteration as 'authentic' is a fool's errand."

"Delicious" is another word I try to avoid. Like "authentic," I'm just not convinced it means much. Unlike "authentic," everyone knows the definition: "this food is good." But it doesn't tell you what is good about it, or why it's good. That unfocused vagueness is why "delicious" is on many food writers' (and editors') lists of banned words.

I'm not going to tell you the food at BlackBrick, Richard Hales' new Chinese restaurant in Midtown Miami, is "authentic." But I will tell you it is "delicious." And I'll do my best to tell you why.[1]

Miami has long been a Chinese food desert. For decades, the Canton chain – a paradigm of mediocrity – somehow managed to be the standard-bearer. Tropical Chinese stands out, but only as a big fish in a little pond. Hakkasan offers a much more refined experience, and their dim sum is excellent, but the price to value (and excitement) ratio of most of the rest of the Hakkasan experience is out of whack. A host of other contenders – Chef Philip Ho, Chu's Kitchen – come and go, with all the stability of Miley Cyrus. Unlike West Coast meccas like Los Angeles, the Bay Area and Vancouver, we seem to lack the populations to support a thriving Chinese restaurant market. And the waves of hyper-regional Chinese restaurants that New York has enjoyed – Sichuan, Shaanxi, Dongbei, Hunan, Yunnan and more, in addition to the more ubiquitous Cantonese – never really made their way here.

(You can see all my pictures in this BlackBrick - Midtown Miami flickr set).

I suspect Richard Hales felt much the same way. And whether because he saw a market opportunity, or just pined to eat better Chinese food and found nobody else making it, he decided to do what he could to change it. BlackBrick, a self-described "passion project," is the result.[2]

Hales' first project as chef/owner was the fast-casual, pan-Asian Sakaya Kitchen, which opened about four years ago. Serving pork buns and Korean chicken wings may not have been an entirely original notion,[3] but Sakaya distinguished itself by focusing on quality ingredients (local and organic whenever possible), fresh preparations, and bold flavors, especially the smoky heat of Korean kochujang that weaves through several dishes.

BlackBrick in some ways follows a similar model, though the service is sit-down style, and the flavor profiles look to China's Sichuan province, among other places, for spicy inspiration. Indeed, if you grab a spot at the counter in front of the open kitchen, you may periodically be inundated by billowing clouds of chili-infused smoke emanating from the wok station.

You can start with something simple and invigorating, like these chicken thighs doused in a spicy chili oil and Chinkiang vinegar, then showered with slivered green onions, cilantro, peanuts and sesame seeds. The poached chicken is served cold with its slippery skin intact, the mild, tender meat a foil for the double dose of spice and sour from the chili oil and black rice vinegar.

"Ma La." These are two more words you're going to want to know. They mean "numbing" and "hot," and their combination – in the form of Sichuan peppercorn (which causes a tingly, numbing sensation) and dried chilies – produces a compulsively tasty, "hurts so good" reaction. It's what makes BlackBrick's "Numbing and Hot Chinese Spare Ribs" so flavorful, the meaty riblets served crusted with dry spice along with wok-sauteed onions, jalapeños and bell peppers.

(continued ...)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)